|

|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

|

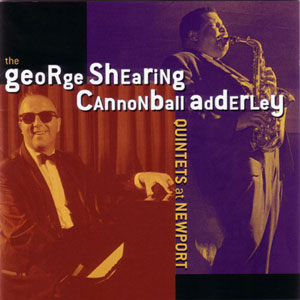

"LIVE AT NEWPORT" |

![]()

|

|

Original cover CD Pablo PACD 5315 |

Reissue

Tracks #1-5

CANNONBALL ADDERLEY-alto sax

NAT ADDERLEY-cornet

JUNIOR MANCE piano

SAM JONES-bass

JIMMY COBB -drums

Track #6-11

GEORGES SHEARING QUINTET

+ track #9 CANNONBALL ADDERLEY-alto sax

+ track #9 NAT ADDERLEY-cornet

1. Wee Dot 7:29

2 .A Foggy Day 6:18

3. Sermonette 3:33

4 .Sam's Tune 6:52

5. Hurricane Connie 4:08

6 . Pawn Ticket 5:35

7 . It Never Entered my Mind 4:06

8 . There Will never be another you

9 . Soul Station 9:18

10 . OLd DeviL moon 5:04

11 . Nothin' But de best 6:05

Soul Station sounds like "Porky" ( Cannonnball Enroute Sessions)

|

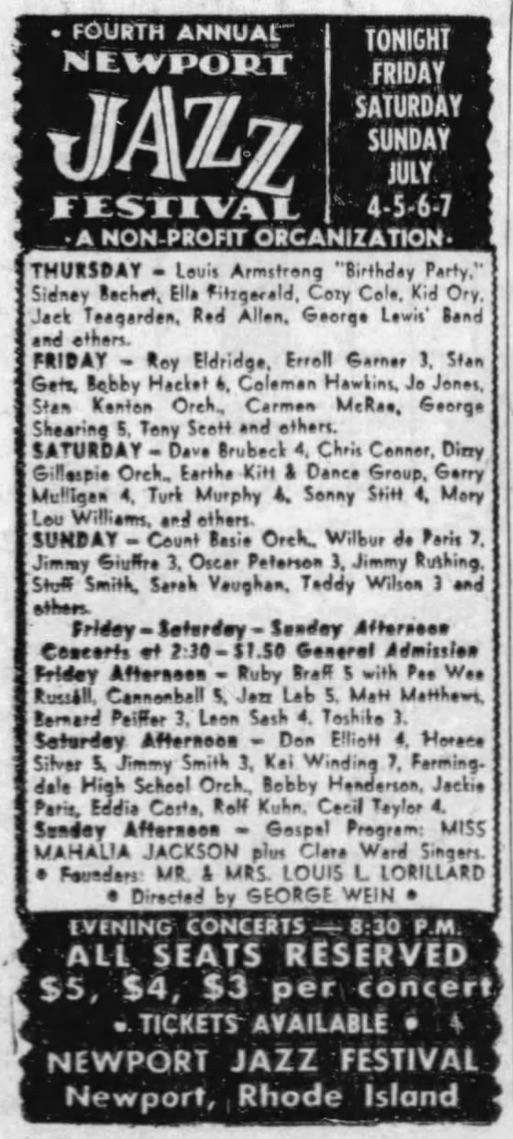

Recorded in Performance at the 4th Newport Jazz Festival , July 5, 1957 |

|

AT NEWPORT is a consequential addition to the prolific and distinguished discographies of Julian "Cannonball" Adderley and George Shearing, who play back to back and briefly join forces on the concert documented herein. The venue is the Newport Jazz Festival, then in its fourth summer, and the bands let their hair down, playing well-paced, tightly arranged, improvisationally open sets before a relaxed, enthusiastic audience under the stars. Observers in 1957 might have found the matchup of Shearing—38, white, English, an established megastar—and Adderley—28, black, Southern, struggling to ascend the jazz tree—to be counterintuitive. But in retrospect, they were complementary personalities. For one thing, they shared a manager, John Levy, the black bassist and road manager of Shearing's first quintet, who left in 1951 to pursue a distinguished and pioneering career in personal management. More to the point, each was an instrumental virtuoso with a populist sensibility, conversant with a full timeline of jazz vocabulary, informed by the imperative to present even the most esoteric music in an unfailingly communicative manner. One evening precisely two years earlier, Adderley had famously exploded on the scene when he sat in with bassist Oscar Pettiford before an enthralled audience of musicians and hipsters at the Cafe Bohemia in Greenwich Village. This happened months after Charlie Parker's death, and such contemporaneous young lions as Jackie McLean and Phil Woods were on record in referring to Adderley's style— he incorporated the harmonic and rhythmic innovations and propulsive thrust of Charlie Parker, with a big, fat Willie Smith lead alto tone, ferocious execution reminiscent of Earl Bostic, and an ability to conjure elegant melodic lines à la Benny Carter—as the next step in extending the vocabulary of the alto saxophone. Adderley grounded his narratives in the tropes of bebop, blues, and the black church, apportioned in equal measure; after the band tears through J.J. Johnson's 1947 composition "Wee Dot," his patter provides a window to his thinking. "That, of course, was a blues, which we like to play very much," says the former high school band director. "You'll find it obvious in our performance here this afternoon, because we feel that the blues reflects what jazz should be made of." Throughout their half-hour set the Adderley Quintet (with Cannonball's cornetist sibling Nat) manifest the trademark collective focus, instrumental prowess, soulful intelligence, and insouciant precision that sealed their popularity with black audiences from the moment they convened in early 1956. Those qualities were due in no small part to the contributions of pianist Junior Mance, bassist Sam Jones, and drummer Jimmy Cobb, a seasoned young rhythm section that could go primal or delicate at the drop of a hat. In particular, Chicagoan Mance uncorks some big-time solos—think Earl Hines and Albert Ammons mixed with Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk—that show us why Lester Young, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, and Dinah Washington had made him their road pianist of choice in previous years. The repertoire—"A Foggy Day" (an insistent medium groove, with telling key modulations), "Ser-monette" (a Ray Charles-inspired bop-shuffle), "Sam's Tune" (a train song), and "Hurricane Connie" (ingenious, warp-speed rhythm changes)—comes from Cannonball Enroute, To the Ivy League with Nat, and Introducing Cannonball Adderley, all recorded for Mercury-EmArcy, a label that kept the brothers in the studio, but backed their product insufficiently. Indeed, Cannonbal's bandstand optimism and ebullience flies in the face of the dire circumstances that already faced him. Owing back taxes, the brothers were deep in debt and would disband temporarily in the winter of 1958, when Cannonball joined forces with Miles Davis and John Coltrane. By contrast, Shearing was at a popular peak. A blind prodigy from a working-class family in London, the pianist had carved out a successful career in England before emigrating to the United States in 1947. Under the sponsorship of countryman Leonard Feather, he quickly made his bones on 52nd Street, establishing props in a popular trio with Oscar Pettiford and J.C. Heard, and sharing bills with prestigious artists ranging from Charlie Parker to Machito. Influenced in formative years by Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum, and Nat Cole, and fascinated with the vocabulary of Romantic and Impressionist European music, Shearing quickly transmuted the vocabulary of bebop into his own voice. Already a fixture in 1949, Shearing became a major star that year when his recording of "September in the Rain" (MGM) with a vibraphone-guitar-piano-bass-drums configuration sold 900,000 copies, imprinting the "Shearing sound"—the vibraphone played the top register of the octave, the guitarist played the bottom, and the piano navigated between those registral boundaries with block chord variations—on the collective consciousness of jazz. In 1955, he signed with Capitol Records, cementing his stature with a series of nuanced, well-promoted albums that showcased his exquisite touch and harmonic ingenuity in a range of contexts. With enviable panache and sophistication, he tackled the fiery complexities of bebop and Afro-Cuban music, intimate solo piano recitals, dialogues with singers Nat Cole, Mel Torme, and Peggy Lee, and plush concerti against mellow backdrops of strings and woodwinds. Here, Shearing's stylistic flexibility is on full display. For his spread-out Newport audience, he eschews, with one exception, the intimate, tasteful arrangements "for very small rooms" that comprised the bulk of his work in 1957. That exception is "It Never Entered My Mind," on which he superimposes the melody of Erik Satie's "Gymnopedie." Otherwise, burning is the order of the night, and the excellent band rises to the task. On "Pawn Ticket"—a worthy entrant in the Ray Bryant lexicon of catchy tunes with slick changes—Shearing unleashes his bop chops on a block chord solo. A stirring "There Will Never Be Another You" features vibraphonist Emil Richards—the multiple percussion maestro who succeeded malleters Don Elliott, Joe Roland, and Cal Tjader in Shearing's units—over sweet fills from classy trapsetter Percy Brice. Shearing learned clave from Machito, and—with idiomatic support from bassist Al McKibbon, himself a disciple of Chano Pozo with Dizzy Gillespie, and from legendary Cuban hand drummer Armando Peraza—customarily climaxed sets with idiomatic Latin flagwavers. McKibbon provides the vamp that propels "Old Devil Moon," and Peraza puts intriguing mambo beats on "Nothin' But De Best," an engaging calypso authored by former Shearing drummer Denzil Best. A stickler for playing charts just precisely so, Shearing required sidemen to read immaculately and to improvise and express their personality when called upon to do so. "We are not usually in the habit of inviting guests up to play with the quintet, because normally we have things completely set," he remarks before summoning the Adderleys on stage. "But we are about at this time to embark on a very special arrangement. As a matter of fact, we are going to arrange it right now." McKibbon and Brice set the tempo, and the impromptu crew launches into "Soul Station," a funky blues line with a Horace Silver connotation. The Adderleys soar, Richards uncorks a cogently jagged declamation, and Shearing lets it all hang out with several intense choruses of block chords, the way he might have done on a third set at Birdland following, say, Bud or Bird or Machito or the Ellington Orchestra. Catching his breath in the aftermath, he briefly sheds his unflappable stage persona, saying, "You don't mind us enjoying ourselves for one night, do you? Whew!" Neither Shearing nor Junior Mance can recall whether this was the only musical encounter of the two John Levy clients. But it was a special one, and both giants honored themselves in the process. Ted Panken

|