|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

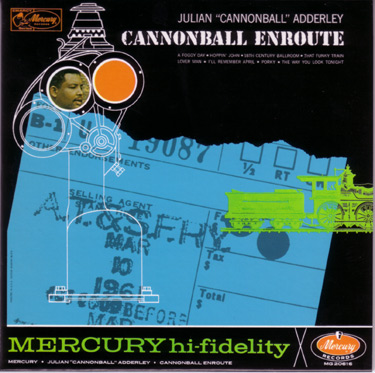

"CANNONBALL ENROUTE" |

![]()

|

|

Original cover LP Emarcy MG20616 |

Other reissue

|

Very rare reissue from Japan

Cannonball Adderley (as)

Nat Adderley (cornet)

Junior Mance (piano)

Sam Jones (bass)

Jimmy Cobb (drums)

1. A FOGGY DAY 3:44

2. HOPPIN' JOHN 4:33

3. 18TH CENTURY BALLROOM 3:32

4. THAT FUNKY TRAIN 5:45

5. LOVER MAN 3:52

6. I'LL REMEMBER APRIL 5:28

7. PORKY 3:34

8. THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT 4:21

|

Recorded in N.Y. February ,1957 (1-2-3-5) , February 7 ,1957 ( 7 ) February 8 ,1957 (7-8) |

|

In the classification-conscious land of jazz, Julian Adderley defies categorization. His music isn't pretentiously intense. It isn't devoid of wit. Adderley, the man, isn't pompous regarding his accomplishments or aims. He doesn't confine his interests to his music; his considerations are worldly and perceptively so. He is a musician, certainly, and a composer-arranger, too. Yet he manages to conduct a radio program, write a column and make innumerable appearances as an articulate spokesman for jazz. He is constantly approachable, eager to discuss matters ranging from Ornette Coleman to international political affairs. His presence on the jazz scene is both refreshing and invaluable. Towering over many of his barely-coherent contemporaries, Cannonball manages to sustain his sense of humor without debasing the music he plays. His playing can be deeply introspective, meaningfully searching-without ever being obscure. Deeply rooted in jazz and aware of its history, Cannonball cherishes the past, carefully examines the present and moves imaginatively toward the future with more regard for esthetics than opportunistic avant garde eccentricity. Cannonball is an individualist. Don DeMichael, Managing Editor of Down Beat, reviewing an Adderley album two years ago, affirmed Cannonball's "right to be called THE boss of the altos . . . Cannonball is not, nor has he ever been, Parker. Bird is dead. But for a time he had some Parkerisms, which made the title seem fitting. Not so now. It's true that he has incor porated some facets of Parker into his playing, but Adderley has gained an identity and individualism that none of the other neo-Parkerites has attained. Adderley displays a wide scope in his choice of tunes; not depending on the standards of modern jazz, he instead deals with unfamiliar material and proceeds to play it very well. His long, sometimes intricate, lines swing and, more importantly, make sense . . . He is a happy man. No morose or dark, ominous playing for him." Since he first invaded the New York jazz in-group in the summer of 1955, departing his Florida home for the more competitive environment of the biggest jazz colony, Cannonball rarely has faltered. His playing, like his personality, has been firm, enlightened and joyous. While many of his cohorts have fingered bitter messages on their horns, Cannonball has continued to celebrate the rewards of life on his. As an alto man (he has played tenor, trumpet, clarinet and flute, too), he's been a force in jazz since that initial trek to Sit in with Oscar Pettiford's group at New York's Bohemia. Except for a stint with Miles Davis' group, he's spent much of his time co-leading a combo with his cornet-playing brother Nat. Few brothers could be as compatible. Nat, a witty extrovert, is as aware of jazz history as is Cannonball. Their musical aims are similar. At 29, he's three years younger than his alto-wielding brother. Chicago-born pianist Junior Mance has, at 32, paid his dues. He's worked with Gene Ammons, Lester Young, and Dizzy Gillespie. He served as accompanist to Dinah Washington. During most of 1956 and 1957, he was a stalwart in the Adderley quintet. A polished modern stylist, he inspired the following words from critic Ralph Gleason: "He is so steeped in the blues tradition that he carries it along everywhere . . . his solos are beautifully constructed, rhythmically as well as melodically." Bassist Sam Jones, 36, hails from Florida, too (Jacksonville), but has spent most of his jazz time in New York, working with Les Jazz Modes, Kenny Dorham, Illinois Jacquet, Cannonball, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk and others. A strong, reliable bassist, he is an asset to any group in need of a firm rhythmic base. Drummer Jimmy Cobb has, since summer, 1958, been a valuable cog in the Miles Davis group. Also 32, he is a quick-handed, discreet drummer, a member of the team, more concerned with group sound than individual action. As a result, he's much in demand for recording sessions at which the horn men wish to be heard. As a valuable sideman with Cannonball's own group, Jimmy asserted his skill in highlighting the alto man's virtuosity without intruding. This is a session notable for the cohesion of the group. Having worked together, the members had developed nuances and understanding. What emerges is a group sound, with individuals featured but never in a struggle to be heard. Everything, as they say, is cool, all around. The opener, 78th Century Ballroom, was composed by Nat Adderley and the inventive pianist Ray Bryant. Listen to Nat, Cannonball and Mance explore, in solos, its flowing motif. Lover Man, the standard that has fascinated many of the alto men of jazz, is in Cannonball's hands between ensemble statements; it is in capable hands. The Gershwins' A Foggy Day is a pulsating London air, with the brothers ably dominating the solo space. Nat's Hoppin' John hops indeed, from Mance's fleet introduction through the solos and exchanges with Cobb to the hopping-off close. The Jerome Kern-Dorothy Fields gem, The Way Tou Look Tonight, sandwiches statements by Cannonball, Julian and Mance between ensembles. The brothers' Porky surges, with Nat perkily opening, Jones talking vigorously, Cannonball having his say and the group getting together for a Dixie-ish climax, complete with tag. Nat's That Funky Train is an estimable excursion into the land of soul, with the rhythm Section providing the reasonable facsimile of the train and Jones, Mance and Nat tooting their own messages. Another pop standard, I'll Remember April, provides a bright frame for the expert solos of the brothers and Mance. It's a tightly-knit, happy session, in keeping with the Adderleys belief in swinging their merry way. Don Gold , Associate Editor, playboy magazine

|