![]()

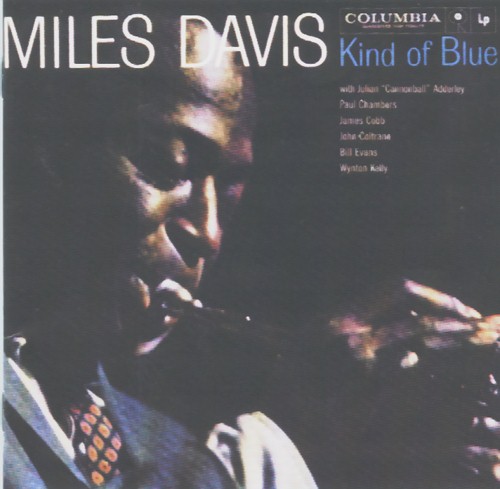

"Kind of Blue" |

![]()

|

Miles Davis (tr), John Coltrane (ts), Julian "Cannonball" Adderley (as), Bill Evans (p), Paul Chambers (b), Jimmy Cobb (d), Wynton Kelly (p). Kelly on "Freddie Freeloader" only. Adderley lays out on "Blue in Green".

New version (CK 64935) contains a bonus alternate take of "Flamenco Sketches".

1. So What

2. Freddie Freeloader

3. Blue in Green

4. All Blues

5. Flamenco Sketches

Following are Bill Evans’ liner notes from the original 1959 LP release:

Improvisation in Jazz by Bill Evans:

There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

The resulting pictures lack the complex composition and textures of ordinary painting, but it is said that those who see will find something captured that escapes explanation. This conviction that direct deed is the most meaningful reflection, I believe, has prompted the evolution of the extremely severe and unique disciplines of the jazz or improvising musician.

Group improvisation is a further challenge. Aside from the weighty technical problem of collective coherent thinking, there is the very human, even social need for sympathy from all members to bend for the common result. This most difficult problem, I think, is beautifully met and solved on this recording.

As the painter needs his framework of parchment, the improvising musical group needs its framework in time. Miles Davis presents here frameworks which are exquisite in their simplicity and yet contain all that is necessary to stimulate performance with a sure reference to the primary conception.

Miles conceived these settings only hours before the recording dates and arrived with sketches which indicated to the group what was to be played. Therefore, you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances. The group had never played these pieces prior to the recordings and I think without exception the first complete performance of each was a "take."

Although it is not uncommon for a jazz musician to be expected to improvise on new material at a recording session, the character of these pieces represents a particular challenge.

Briefly, the formal character of the five settings are: "So What" is a simple figure based on 16 measures of one scale, 8 of another and 8 more of the first, following a piano and bass introduction in free rhythmic style. "Freddie Freeloader" is a 12-measure blues form given new personality by effective melodic and rhythmic simplicity. "Blue in Green" is a 10-measure circular form following a 4-measure introduction, and played by soloists in various augmentation and diminution of time values. "All Blues" is a 6/8 12-measure blues form that produces its mood through only a few modal changes and Miles Davis' free melodic conception. "Flamenco Sketches" is a series of five scales, each to be played as long as the soloist wishes until he has completed the series

Kind of Blue by Robert Palmer:

Playing gigs at the Fillmore East during the sixties made it easier for you to get in and catch other bands, even if tickets were sold out. As a young saxophonist in a rock band, I played there several times and attended numerous concerts; the one group I never missed (unless I had to be on the road) was the Allman Brothers Band. More specifically, I went to see their guitarist, Duane Allman, the only "rock" guitarist I had heard up to that point who could solo on a one-chord vamp for as long as half an hour or more, and not only avoid boring you but keep you absolutely riveted. Duane was a rare melodist and a dedicated student of music who was never evasive about the sources of his inspiration. "You know," he told me one night after soaring for hours on wings of lyrical song, "that kind of playing comes from Miles and Coltrane, and particularly Kind Of Blue. I've listened to that album so many times that for the past couple of years, I haven't hardly listened to anything else."

Earlier, I'd met Duane and his brother Gregg when they had a teenage band called the Hourglass. One day I'd played Duane a copy of Coltrane's Olé, an album recorded a little more than a year after Kind Of Blue but still heavily indebted to it. He was evidently fascinated; but a mere three or four years later, at the Fillmore, I heard a musician who'd grown in ways I never could have imagined. It's rare to see a musician grow that spectacularly, that fast; I'm not sure there's any guitarist who's come along since Duane's early death on the highway who has been able to sustain improvisation of such lyric beauty and epic expanse. But the influence of Kind Of Blue, even to the point of becoming a kind of obsession, wasn't unusual at all; it was highly characteristic of musicians of our generation, mine and Duane's. Of course, listening to an album isn't going to turn anyone into a genius; you can't get more out of the experience than you're capable of bringing to it. Duane brought something special, even unique to the table, but it seemed that everyone was sharing the meal. This was true among musicians categorized as "rock" or "pop" as well as among those labeled "jazz." In fact, the influence of Kind Of Blue has been so widespread and long-lasting, it's doubtful that anyone has yet grasped its ultimate dimensions. We know Kind Of Blue is a great and eminently listenable jazz album, "one of the most important, as well as sublimely beautiful albums in the history of jazz" in the words of Miles biographer Eric Nisenson. But there is more to it than that.

Music fans, not to mention critics and even more musicians, can be an opinionated and contentious bunch, even when it comes to works and artists almost universally admired as classics. It often seems no "great work" is sacrosanct. Not all rock aficionados share a high opinion of the Beatles' opus Sgt. Pepper, for example; to some, it's uneven, self-indulgent, overproduced, underwritten--and dated, a flower-power curio. The recent elevation of the late Robert Johnson to "King of the Delta Blues" has provoked grumbling from some scholars, who point out that Johnson sold few records in his lifetime and was never as influential among other musicians as Charley Patton, Son House, or even Muddy Waters. Or consider the case of John Coltrane, whose breathtaking solos on Kind Of Blue would seem to be an integral aspect of its charms. One influential critic, Martin Williams, gives Ornette Coleman his due but includes only one brief and somewhat atypical performance by any of Coltrane's bands on The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz. There's no "Giant Steps," no "Chasin' the Trane," no "A Love Supreme"--all, presumably, "classic" jazz.

Kind Of Blue distances itself from even this exclusive company by having few, if any, notable detractors. Of course, we can always depend on at least some critics to miss the boat on its maiden voyage, and in fact, some early reviews of the album described Miles' playing as "morose," "maudlin," even "sluggish (!) and low in energy output." But a number of critics immediately recognized Kind Of Blue as a modern masterpiece, and in recent years little has been heard to the contrary. Not even the sort of after-the-fact analysis that has managed to make certain other recorded masterworks all-too-familiar, draining them of a great deal of their "magic" or "charge," has dimmed the luster of Kind Of Blue. Miles Davis never liked "explaining" his music, and when it comes to Kind Of Blue, the other musicians he chose as participants have managed to avoid analyzing the proceedings to death. Somehow, the experience of Kind Of Blue insists on retaining at least a touch of the ineffable.

Consider the circumstances. Miles took his musicians into the studio for the first of two sessions for Kind Of Blue, in March, 1959. At the time, "modal" jazz--in which the improviser was given a scale or series of scales (or "modes") as material to improvise from, rather than a sequence of chords or harmonies--was not an entirely new idea. Miles himself had tried something similar in 1958 with his tune "Milestones" (also known as "Miles") and when he and Gil Evans were recasting the songs from Gershwin's Porgy And Bess around that time, they rewrote "Summertime" to include a long modal vamp, with no chord changes. Originally, the idea for this kind of playing was the concept of composer George Russell, but his program for "modal jazz" came imbedded in an elaborate, all-embracing musical/philosophical theory, the "Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization." Miles saw the approach, at least in part, as a way of drastically simplifying modern jazz, which was then pushing against the outer limits of chordal complexity. "The music has gotten thick," Davis complained in a 1958 interview for The Jazz Review. "Guys give me tunes and they're full of chords. I can't play them…I think a movement in jazz is beginning away from the conventional string of chords, and a return to emphasis on melodic rather than harmonic variation. There will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them." Technical though it may seem to nonmusicians, Davis' statement can be reduced to a single, simple proposition: a return to melody. Kind Of Blue is, in a sense, all melody--and atmosphere. In essence, Miles Davis was looking for new forms that would encourage his musicians to improvise in streams of pure melody, which is an aspect of music as easily appreciated by the layman as by those who speak modal.

It's worth noting that Miles didn't just write out some simple, almost skeletal compositions, pass them around the band, and hope for the best. He chose his players carefully, bringing back the already departed pianist in his sextet, Bill Evans, for these sessions only. His group's new pianist Wynton Kelly was something of a blues specialist, and he was asked to play on one tune only, the blues "Freddie Freeloader." Some of the musicians credit Miles with "psyching" Kelly into playing that would fit seamlessly alongside Evans' work on the rest of the album. Perhaps. As Nisenson points out in his 'Round About Midnight, "The recording in and of itself was an experiment. None of the musicians had played any of the tunes before; in fact Miles had written out the settings for most of them only a few hours before the session... In addition, Miles stuck to his old recording procedure of having virtually no rehearsal and only one take for each tune." Nisenson quotes drummer Jimmy Cobb as saying of Kind Of Blue, "It must have been made in heaven," which may be as revealing an explanation as we're ever going to get. Because there is something transcendent, poetic, perhaps even heavenly about the music on Kind Of Blue. To check it out, go right to the only unused first take of the sessions, the alternative version of "Flamenco Sketches."

On any other Miles Davis album, the first, previously unheard take of "Flamenco Sketches " (the last selection on this disc) would have been a highlight. Listened to on its own, it is a group performance of the highest quality. The supple strength and firmly-centered tone of Paul Chambers' bass (heard here with a clarity unmatched by earlier reissues) is much the same on both performances. So is the precise clarify and unquenchable swing of Cobb's drumming. The solos by Miles, pianist Bill Evans, and saxophonists John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley are different from the solos on the familiar, issued version of "Flamenco Sketches," as one would expect from improvisers of this caliber. Adderley, however, can be heard formulating and organizing melodic materials that coalesce into an altogether different sort of melodic statement on his second try, the issued take. And this, it seems to me, is precisely where Kind Of Blue comes into its own as a monument to sheer inspiration and creativity. Every solo seems to belong just as it is; it isn't so much theme-and-variations or a display of virtuosity as it is a king of singing.

Kind Of Blue flows with all the melodic warmth and sense of welcoming, wide-open vistas one hears in the most universal sort of song, all supported by a rigorous musical logic. For musicians, it has always been more than some beautiful music to listen to, although it is certainly that. It's also a how-to, a method for improvisers that shows them how to get at the pure melody all-too-frequently obscured by "hip" chord changes or flashy fingerwork. But no matter how much a musician or a listener brings to it (for this is one of those incredibly rare works equally popular among professionals and the public at large), Kind Of Blue always seems to have more to give. If we keep listening to it, again and again, throughout a lifetime--well, maybe that's because we sense there's still something more, something not yet heard.

Or maybe we just like paying periodic visits to heaven.

-Robert Palmer