|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

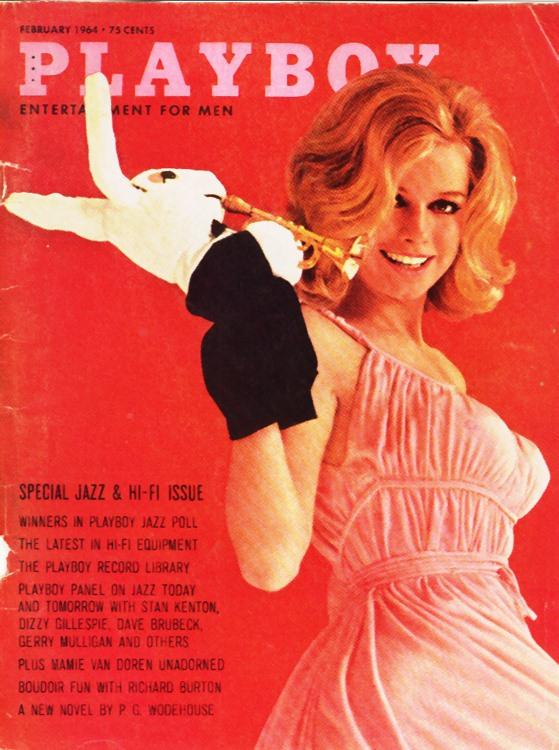

THE PLAYBOY PANEL: JAZZ-TODAY AND TOMORROW |

![]()

|

From the February 1964 issue .

|

|

THE PANEL LIST JULIAN "CANNONBALL" ADDERLEY is an urbane alto saxophonist and leader who has achieved sizable popular success during the past five years. He is also a recording director and has helped many musicians get their first chance at national exposure. Adderley has termed his music "modern traditional," indicating his knowledge and respect for the jazz past as well as his interest in continuing to add to the music. Through his lucid, witty introductions at concerts, festivals and night clubs, Adderley has become a model of how to make an audience feel closer to the jazz experience. DAVE BRUBECK, the rugged, candid pianist, leader and composer, has won an unusually large audience to the extent of even having had a number of hit single records. Instead of coasting in a familiar groove, however, he has continued to experiment; in recent years he has turned to time signatures comparatively new to jazz. Although Brubeck is characteristically friendly and guileless, he is a fierce defender of his musical position and does not suffer critics casually. JOHN "DIZZY" GILLESPIE is now recognized throughout the world as the most prodigious trumpet player in modern jazz. He is also the leading humorist in jazz and he has demonstrated that a jazz musician can be a brilliant entertainer without sacrificing any of his musical integrity. He is now leading one of the most stimulating groups of his career, and is also engaged in several ambitious recording projects. RALPH J. GLEASON, one of the few jazz critics widely respected by musicians, is a syndicated columnist who is based at the San Francisco Chronicle (in our October issue, we erroneously placed him on the Examiner staff). He has edited the book Jam Session; has contributed to a wide variety of periodicals, in America and abroad; and is in charge of Jazz Casual, an unprecedentedly superior series of jazz television shows, distributed by the National Educational Television Net work. As a critic, Gleason is clear, some times blunt, and passionately involved with the music. STAN KENTON is a leader of extraordinary stamina and determination. He has created a distinctive orchestral style and, in the process, has given many composers and arrangers an opportunity to experiment with ideas and devices which very few other band leaders would have permitted. The list of Kenton alumni is long and distinguished. In a period during which the band business has been erratic at best, Kenton is proving again that a forceful personality and unmistakably individual sound and style can draw enthusiastic audiences. CHARLES MINGUS, a virtuoso bassist, is one of the most original and emotionally compelling composers in jazz history. His groups create a surging excitement in producing some of the most startling experiences jazz has to offer. He is also an author, and has completed a long, explosive autobiography, Beneath the Underdog. An uncommonly open man, Mingus invariably says what he feels and continuously looks for, but seldom finds, equal honesty in the society around him. GERRY MULLIGAN has proved to be one of the most durable figures in modern jazz. In addition to his supple playing of the baritone saxophone, he has led a series of intriguingly inventive quartets and sextets as well as a large orchestra which is one of the most refreshing and resourceful units in contemporary jazz. Mulligan also has acted in films and is now writing a Broadway musical. He has a quality of natural leadership which is manifested not only in the way all of his groups clearly reflect his musical personality, but also in the fact that whenever jam sessions begin at jazz festivals, Mulligan is usually in charge. GEORGE RUSSELL has emerged during the past decade as a jazz composer of exceptional imagination and originality. He has recorded a series of albums with his own group, and these represent one of the most impressive bodies of work in modern jazz. He is also a teacher, and among his students in New York are a number of renowned jazzmen. A pipe- smoking, soft-voiced inhabitant of Green wich Village, Russell is not one of the more prosperous jazzmen, despite his stature among musicians, but he refuses to compromise his music in any way. GUNTHER SCHULLER is a major force in contemporary music - both classical and jazz. He is one of the most frequently performed American composers, has been awarded many commissions here and abroad (his most recent honor, a Guggenheim fellowship), and is also an accomplished conductor. For ten years, Schuller was first French horn with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, but now devotes his full time to composing, conducting and writing about music. He has had extensive experience in jazz and is largely responsible for the concept of "third-stream music." He is currently working on an analytical musical history of jazz for Oxford University Press. A man of seemingly limitless energy, Schuller is expert in many areas of music as well as in literature and several of the other arts.

BRUBECK: I don't think there's much of a connection between how much is written in newspapers and magazines about jazz and the growth of its audience. After all, if this were important, classical music would have a much larger audience than pop music. Yet you can't compare the record sales of even the most popular classical artists, such as Leonard Bernstein with those of Johnny Mathis. Now let's carry this over to jazz; certainly there's more being written today about jazz musicians, but I don't think it will affect the popularity of the jazz musician much, or his record sales, or the amount of work he gets. As for work being harder and harder to find, I think this is true. Not true for the accepted jazz musicians, the ones who have been around for a while. I'd say the pianists I feel are my contemporaries- Erroll Garner, George Shearing, Oscar Peterson - are certainly working as much as they want to work. I am, too. You couldn't say we're complaining. But a young pianist coming up today might have a harder time than we did. GLEASON: While it is true that several night clubs have gone out of business - night clubs that have been associated with jazz over the years - I don't think jazz is in any economic decline. The sales of jazz records and the presence of jazz singles on the hit parade indicate it isn't. The box-office grosses of the New- port Jazz Festival and the Monterey Jazz Festival indicate it isn't. The proven drawing ability of groups like those led by Miles Davis, Count Basie, John Coltrane - and from this panel, Brubeck, Dizzy and Cannonball Adderley - show that there is a very substantial market for jazz in this country. But there is not a market for second-

rate jazz, and at certain times in the past, we have had an

economy that has supported second-rate jazz as well as first-rate

jazz. I think that those fringe groups are now finding work

difficult to get. On the other hand, all the jazz night clubs

complain consistently that it's hard to find top-caliber acts to

fill out a 52-weeks-a-year schedule. Jazz is, of course,

receiving a great deal of publicity these days, in MULLIGAN: I think this all has to be seen in perspective. During the big upsurge of jazz in the early 1950s, we saw a tremendous increase in the number of clubs. Now we start wailing the blues and we say, look how terrible times are when these clubs start to close. But we forget that what has happened is that the business has settled back to normal. I'd imagine that there are probably more jazz clubs today than there were in the 1930s. I think you'd find that there were many fewer units in the Thirties and probably none of them was making the money that even some relatively unknown groups are making today. RUSSELL: I can't agree with the optimism that has been expressed so far. I think economic conditions are bad for all but the established groups, and the reason goes to the basic structure of American life. During the swing era, anti-Negro prejudice was at a vicious level. So the young Negro rebels, intellectuals and gang members alike, shared a reverence for jazz because it expressed the feelings of revolt that they needed. It seemed that they had to feel that at least some-thing in their culture was a dynamic, growing thing. The creative jazz musician was one of the most respected members of the Negro community. Then bop came along and was generally accepted by the culturally unbiased dissidents and rejected by those committed to status goals - in either case, irrespective of race. Another conflict was added to jazz which also transcended race - between the innovator who creates the art (seeking what he can give to it), and the imitator who dilutes and who is mostly interested in what art can give to him. There is, to be sure, a revolution going on in America. People want an equal chance to compete for status goals that compromise rather than enhance a meaningful life. What I would like to see is a renaissance. Shouldn't a social revolution be armed with a violent drive not only to elevate the individual, but to elevate and enrich the culture as well? If we continue to cater to the tyranny of the majority, we shall all be clapping our hands to Dixie on one and three. MINGUS: You have to go further than that. No matter how many places jazz is written up, the fact is that the musicians themselves don't have any power. Tastes are created by the business interests. How else can you explain the popularity of an Al Hirt? But it's the musicians' fault for having allowed the booking agents to get this power. It's the musicians' fault for having allowed themselves to be discriminated against. SCHULLER: I'll go along with George and Charles that there are serious economic problems in jazz today, but the basic answer is very simple. It's not a comforting answer economically, but I believe that jazz in its most advanced stages has now arrived precisely at the point where classical European music arrived between 1915 and 1920. At that time, classical music moved into an area of what we can roughly call total freedom, which is marked by such things as atonality, or free rhythm, or new forms, new kinds of continuity, all these things. So the audience was suddenly left without a tradition, without specific style, without, in other words, the specifics of a language which they thought they knew very well. By also moving into this area - and I believe the move was inevitable - jazz has removed itself from its audience. ADDERLEY: I don't know about that. There is an audience out there now, a sizable audience. But you have to play for it. When we go to work, we play for that audience because the audience is the reason we're able to be there. Of course, we play what we want to and in the way we want to, but the music is directed at the audience. We don't play for ourselves and ignore the people. I don't think that's the proper approach, and I've discovered that most of the guys who are making a buck play for audiences. One way or another.

ADDERLEY: Well, I think the audience feels quite detached from most jazz groups. And it works the other way around, too. Jazz musicians have a tendency to keep themselves detached from the audience. But I speak to the audience. I don't see that it's harmful to advise an audience that you're going to play such and such a thing and tell them something about it. Nor is it harmful to tell something about the man you're going to feature and something about why his sound is different. Or, if somebody requests a song we've recorded with some measure of success, we'll program it. GILLESPIE: Yes, I think some jazz artists are forgetting that jazz is entertainment, too. If you don't take your audience into consideration and put on some kind of a show, they'd just as soon sit at home and listen to your records instead of coming to see you in person.

KENTON: For big bands, there does seem to be a trend away from the clubs, because so many of the clubs have had such problems trying to keep alive. We might finally be left with only concert halls - where you can book spotty dates. But personally, I really don't see a lot of difference between clubs and concerts so long as you can play jazz for listening. I don't think most of us mind whether people are drinking while they listen or whether they're just sitting in a concert hall. I'd just as soon play in either context. GLEASON: I don't think the future of jazz lies largely in the concert field. I think that it lies partially in the concert field and partially in the night clubs. The fact that Brubeck and Erroll Garner and the Modern Jazz Quartet have all reached a level of economic independence where they can function outside the night club most of the time is an indication of their success, not necessarily an indication of the future of jazz. All the jazz groups I've ever heard have something different to offer when they're in night clubs than they do when they're on the concert stage. I recently heard the Brubeck quartet, for instance, play the first night-club engagement on the West Coast that it's played in probably six or seven years. I came to that night-club engagement after having heard them in two concert appearances, and the thing that happened in the night club was much more interesting and much more exciting than it was in the concert hall. And all four musicians commented on how great they felt and how well the group played in the night club appearance. MINGUS: I wish I'd never have to play in night clubs again. I don't mind the drinking, but the night-club environment is such that it doesn't call for a musician to even care whether he's communicating. Most customers, by the time the musicians reach the secoud set, are to some extent inebriated. They don't care what you play anyway. So the environment in a night club is not conducive to good creation. It's conducive to re-creation, to the playing of what they're used to. In a club, you could never elevate to free form as well as the way you could, say, in a concert hall. BRUBECK: I can understand that feeling. The reason we got away from night clubs has nothing to do with the people who go to night clubs, or night clubs themselves, or night-club operators. It has to do with the way people behave in night clubs. The same person who will be very attentive at a concert will often not be so attentive in a night club. But I must also say that there are some types of jazz I've played in groups which would not come across well in a concert-stage atmosphere. And to tell you the truth, I'm usually happiest playing jazz in a dance half, because there I don't feel I'm imposing my music and myself on my audience. They can stand up close to the bandstand and listen to us, or they can dance, or they can be way in the back of the hall a holding conversation. GILLESPIE: Maybe so, but for myself, the atmosphere in a night club lends itself to more creativity on the part of the audience as well as the musician. One reason is that the musician has closer contact with the people and, therefor can build better rapport. On the other hand, I also like the idea of concerts, because, for one thing: the kids who aren't allowed into night clubs can hear you at concerts and can then buy your records. But to return to the advantag of clubs, when you're on the road a lot ,the club - at least one where you can stay a comparatively long period of time- does give you a kind of simulated home atmosphere. There's a place for both clubs and concerts. ADDERLEY: Yes, I like to play them both too. And I like festivals. I like television shows - any kind of way we get a chance to play consistently. I like to do. But unlike Charles, a joint has my favorite atmosphere. It's true that some people can get noisy, but that's part of it. It seems to me that I feel a little better when people seem to be having a good time before you even begin. And it gives me something to play on. In a concert, sometimes, we don't have enough time to warm up and if the first number is a little bit below our standards, we never quite recover. At least in a club you have sets, and if one set doesn't go well, you have a chance to review what you've done and approach it another way the second time around. My own preferences aside, however, I think that the night-club business general is on an unfortunate decline. a short while, the night club will be a relic, because night clubs are too expesive for most people to really support in the way they should be supported. Just recently, I was talking to a guy who has a club in Columbus, Ohi .Several years ago, he played Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver, Miles Davis, Kai Winding, the Oscar Peterson Trio, and my band. He said he didn't pay over $2200 a week for anybody. But now groups that used to cost him $1250 cost $2500, and the same way up the line. But he has no more seats than he had before, and the people are unwilling to pay double for drinks even though the bands cost the owner double. Yet, at the same time, the musician' cost of living has also gone up. It's a rough circle to break.

ADDERLEY: Not particularly. I think there'll be other things. There'll be theaters. I think festivals are going to come back in a different way. The George Wein type of festival of today stands a good chance. In the purest sense, his are not jazz festivals the way Newport was in the beginning. But if Wein presents somebody like Gloria Lynne at a festival today, whether or not she is a jazz singer isn't the point. The fact is she is going to draw a certain number of people. So Wein, thereby, can also present Roland Kirk and he can call it a jazz festival. Most people are not going to quibble over whether Gloria Lynne is a jazz singer; they'll come to hear her at a jazz festival. MULLIGAN: Well, I want to try whatever outlets for playing we have. I don't want to do the same thing all the time. As for clubs, at any given time, there are maybe only three to five clubs in the country that I really enjoy playing. And when you figure two to three weeks in each of five clubs, about 15 weeks of the year are already taken care of. Fortunately, in New York, there is more than one club in which we can work, so that we can stay there longer. We need that time, because otherwise we'd never get any new material. There are advantages and disadvantages on both sides. I find clubs very wearying in a way in which concerts aren't. The hours themselves working from nine to two or nine to four, what ever it is. It plays hell with your days. I know guys who are able to get work done in the daytime when they're playing clubs. Maybe they're better disciplined than I am, but I find I'm drained by clubs. So that's what concerts can mean to me - a chance to work during the day. But I also need clubs because we need that kind of atmosphere for the band - an atmosphere in which you just play and play and play. The hard work of it - playing hour after hour, night after night, in the same circumstances - is good for a band. Concerts, however, are also good for the big band, because they allow me to do a greater variety of things. And economically, there are very few clubs into which I can take the big band - because of transportation costs and the problems of working out some kind of consecutive tour. So, I have to think in terms of both concerts and clubs. So far as I'm concerned, I don't see my future as exclusively in one or the other direction. MINGUS: I'll tell you where I'd like more of my future work to be. I'd like some Governmental agency to let me take my band out in the streets during the summer so that I could play in the parks or on the backs of trucks for kids, old people, anyone. In delinquent neighborhoods in the North. All through the South. Anywhere. I'd like to see the Government pay me and other bands who'd like to play for the people. I'm not concerned with the promoters who want to make money for themselves out of jazz. I'd much rather play for kids.

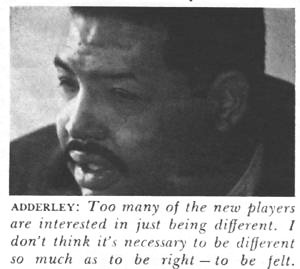

SCHULLER: It's not entirely accurate to relate what's happening now to what took place in the 1940s. The language of "bop" at that time remained largely tonal, and even a comparative novice could connect it with what had gone before in jazz. This is no longer true. The music of the jazz avant-garde has gone across that borderline which is the same borderline which the music of Schoenberg passed in 1908 and 1909. At that time, it was the most radical step in some 700 years of classical music. In jazz, nothing so radical as what has been going on during the past five years took place in the previous 40 or 50 years of jazz history. Everything previously, even the bop "revolution," was more of a step-by-step evolution. What's happening now is a giant step, a radical step. Because of the radical nature of the advance, there is a much greater gap between player and audience now than there was in the 1940s. KENTON: I agree about the gap, but I also feel that a lot of the modern experimenters are taking jazz too fast. Some times they're doing things just to gain attention - being different for the sake of being different. They're also running the risk of losing their audience entirely. After all, if a music doesn't communicate to the public, I don't care how sophisticated a listener may be, eventually he'll lose interest and walk off if there's no communication. The listener might kid himself for a while if he thinks there's something new and different in the music, but if there's no validity to the music, I'm afraid the jazz artist might lose the listener entirely. GLEASON: First of all, I don't think that the jazz of the established players has become too predictable or too safe. What's predictable or safe about the way Miles Davis or Dizzy Gillespie play, or John Coltrane? Secondly, jazz musicians are by nature experimental. Every new generation of jazz musicians will try to do something new. And in trying to do something new, they may do a lot of foolish things and a lot of dull things. They may do a lot of things that will have no interest for other musicians,now or in the future. But this won't stop them from experimenting. BRUBECK: We are certainly in a period during which musicians are starting to branch out into very individualistic directions, and that's very healthy. It's also healthy because we're not codified. It doesn't all have to be bop or swing or New Orleans or Chicago style. We can all be working at the same time in our own individual ways. We are now in the healthiest period in the history of jazz. As for the new generation of young musicians insisting on greater freedom - melodically, harmonically and rhythmically - they certainly should. This is their role - to expand, to create new things. But it's also their role to build on the old, on the past; and when you have all these new, wild things going on, there are some of the wild experimenters who aren't qualified yet. They haven't the roots to shoot out the new branches. They will die. GILLESPIE: That's right. You have to know what's gone before. And another thing, I don't agree that the established players have become too "safe." It takes you 20 to 25 years to find out what not to play, to find out what's in bad taste. Taste is something - like wine - that requires aging. But I'd also agree that jazz, like any art form, is constantly evolving. It has to if it's a dynamic art. And unfortunately, many artists do not evolve and thus remain static. As for me, I'm stimulated by experimentation and unpredictability. Jazz shouldn't be boxed in. If it were, it would become decadent. MINGUS: Any musician who comes up and tries changing the whole pattern is taking too much in his hands if he thinks he can cut Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, King Oliver and Dizzy all in one "new thing." You see, there's a danger of those experimenters getting boxed in themselves in their own devices. As for now, I don't hear any great change in jazz. Twenty years ago, I was playing simple music that was involved with a lot of things these musicians are doing now. And I'm still playing the same simple music. I haven't even begun to play what I call way-out music. I have some music that will make these cats sound like babies, but this is not the time to play that kind of music. ADDERLEY: I agree with that question implies - we've had a certain amount of lethargy in recent years. Everybody knew how to do the same thing. So, I'd like to say thank God for Ornette Coleman and such players because, whether or not you're an Ornette Coleman fan, his stimulus has done much for all of us. I know it caused me to develop. It caused Coltrane to develop even further, because he felt he had exhausted chord patterns and so forth. However, there has also been a focusing on another area - one Dizzy mentioned. I heard a new record by Illinois Jacquet the other day and it made me realize again that as certain guys get older, they develop a tendency to get more out of less. Illinois gets more out of his sound, more out of a little vibrato in the right place than he used to. Therefore, don't discount the maturity that has come with experience and discipline. As I say, many of us have been stimulated by what's going on, but we're also aware that often emotion is missing in all this emphasis on freedom. Too many of the newer players are interested in just being different. I don't think it's necessary to be different so much as to be right. To be felt. To be beautiful. MULLIGAN: Yes, the concept of freedom has been overworked a great deal. In the course of "freeing" themselves, as Mingus said, a lot of the guys have be come even more rigidly entrenched in a stylized approach.

GLEASON: My reaction? Hooray! Let's have third-stream music and fourth- stream music and fifth-stream music and sixth-stream and whatever. Let's just have more music. There's nothing inherently good or bad in the idea of a new kind of music which will draw from various musical heritages. This may turn out to be a very good thing. Some of it has already turned out to be quite interesting. KENTON: I'd agree that music is music, but as for "third stream," I think it's just a kind of merchandising idea. I've been interested in the development, but I don't think there's anything new there. ADDERLEY: Well, I'm the last person to discourage anyone's interest in trying to do something different. However, as much as I respect and admire the willingness of the third-stream people to work hard, their music misses me most of the time. I listen to a lot of classical music, and it seems to me that most of what they're doing with the "third stream" has already been developed further by the more venturesome classical composers. Besides, Duke Ellington has shown us how to develop jazz from within to do practically anything. On the other hand, we know how ridiculous Stravinsky's Ebony Concerto is. MULLIGAN: As Dizzy said, we already use certain devices that can be traced to some kind of classical influence. But this idea of an autonomous music - separate from both jazz and classical music - I don't see any need for it. That's not to say I wouldn't like to write things for, or play with, a symphony, but whether a "third stream" should come along and have its own niche is something else. It seems to me it's going to have to be absorbed into one or the other main stream. RUSSELL: A third stream isn't necessary. In fact, jazz itself may he the main stream of music to come. I mean that, to me, jazz is an evolving classical music. In my own work, I don't draw that heavily on traditional classical standards. I have been influenced by composers like Bartok, Stravinsky and Berg, but if those influences go into my music, it's unconscious. A conscious attempt to combine the two is not my way of doing things. You see, I think jazz itself is the classical music of America, and eventually it will transcend even that role and become, in every profound musical sense, an international classical music. BRUBECK: When wasn't jazz what you describe as third-stream music? Melodically, from the beginning, jazz has been mostly European. Harmonically, it's been mostly European. The forms used have been mostly European. In fact, the first written jazz form was the rag and that was a copy of the European march. I think it's time we realize that we couldn't have had jazz without the merging of the African culture with the European culture. But in the beginning it was primarily a European music transformed to fulfill the expression of the American Negro. Once having acknowledged that, we ought to forget about who did what and when and we ought to forget whether jazz is African or European. Jazz now is an American art form and it's being played all over the world.

SCHULLER: Absolutely, and this is confirmed for me almost every day of my life - especially this past summer at Tanglewood, where I was very much in touch with what you could call a cross section of the young American musical generation. Tanglewood draws its 200 students from all over the country; and even in this citadel of nonjazz music, at least 30 to 40 percent of the young musicians there were in some sense in volved with jazz or could play it. And some of them played it extremely well. Now, these musicians epitomized what I feel about third-stream music, and that is the elimination of a radical barrier or difference between jazz and classical music. To the kids, there is no such big difference. It's all either good or not-so- good music. And the question of jazz style or nonjazz style is not a fundamental issue with them. They deal with much more fundamental musical criteria - is a piece, in whatever style, good or bad? This means that the third-stream movement, whether the critics or certain musicians happen to like it or not, is developing by itself - without any special efforts on anybody's part. ADDERLEY: My feeling, though, is that when you deal with something like third stream, which mixes jazz with classical music, you're going to weaken the basic identity of jazz. SCHULLER: It's true that many people worry about the guts being taken out of jazz as it evolves. They worry about it becoming "whitened." However, jazz has indeed basically changed into some thing different from what it started as. It started as folk music, as a very earthy, almost plainly social expression of a downtrodden people. It then became a dance music, an entertainment music - still with roots in the very essence and heart of life. It was not an art music. Now, as it becomes an art music - and there's no question that it already has in the hands of certain people - it will change its character. The process is in evitable.

KENTON: Yes. Jazz, to start with, is not a popular music at all. It's true that a lot of the bands in the Golden Era of bands were kind of jazz oriented and did quite well playing dance music and swing, but real jazz has no greater following throughout the world today than has classical music. I think we might as well make up our minds that that's the way it's going to be. GLEASON: I don't agree that jazz audiences are going to become smaller and more select. If Count Basie's band and Duke Ellington's band weren't jazz bands, and aren't jazz bands, then I don't know what are. Woody Herman's also. And these hands at various times have had very large audiences. Benny Goodman's biggest successes were scored with bands that were really jazz bands, not just jazz-influenced bands. BRUBECK: That's right. In the late 1930s and the beginning of the 1940s, I saw some tremendous jazz bands with some very large audiences in the interior of California, a place called Stockton, where I was going to college. It's pretty much off the beaten path, so if you could draw large audiences there at that time, you could draw large audiences anyplace in the United States. Duke Ellington was there for a week and he had a full house every night. Jimmie Lunceford was there. Stan Kenton came through. Woody Herman. Count Basie. Now, I wouldn't call those bands jazz influenced. They were influcncing jazz. I think Hodeir is referring to some other bands that may have been more popular, but I hardly think they were that much more popular. The bands then were set up to be more entertaining than we are today - but they were also playing great music. I do agree with Hodeir that jazz is be coming much more of an art music. In other words, we aren't putting on a show and good jazz at the same time. We're each of us putting on our own individual brand of jazz, and it's not meant to be entertaining in the sense that it's a show. But it's entertaining in the sense that it's good music, sincere music that we hope reaches an audience. Maybe this absence of a "show" does put jazz into the art-music category, but I for one wouldn't mind seeing jazz go back to the days of the 1930s when you had more entertaining bands, such as Ellington's. And don't forget that Ellington, while he was entertaining, was also able to create a Black, Brown and Beige. SCHULLER: But jazz is not going to go back to the 1930s. And I maintain that, to the extent that jazz ever has been a really popular music, it has been the result of a certain commercialization of jazz elements. Even with the best of the jazz bands, like Fletcher Henderson's, their style wasn't popular. What be came popular was a certain simplification of that style as it was used by Benny Goodman. ADDERLEY: I don't agree with Hodeir. I don't think jazz ever will cease to be important to the layman, simply because the layman has always looked to jazz for some kind of escape from the crap in popular culture. Anybody who ever heard the original form of Stardust can hardly believe what has happened to it through the efforts primarily of jazz musicians. Listen to the music on television. Even guys who think in terms of Delius and Ravel and orchestrate for television shows draw from jazz. The jazz audience has always existed, and it always will. RUSSELL: I think there'll be a schism in the forms of jazz. There definitely will be an art jazz and a popular jazz. As a matter of fact, that situation exists today. GILLESPIE: I'm optimistic. Yes, the audience will become select, but it won't be small. Let me put it another way: The audience will become larger but it will be more selective in what it likes. SCHULLER: I don't see how. The people who are going to become involved with jazz, as it's developing now, are going to be come very much involved. You just can't take it passively as you could, for instance, the dance music of the bands in the 1930s. You could be comparatively passive about them. But if you're going to be involved with Ornette Coleman at all, you've got to be involved very deeply, or else it goes right past you. We must expect a smaller audience from now on, and there's nothing wrong in that. A sensitive audience is a good audience. Because of what's happened to the music, we can no longer expect the kind of mass appeal that certain very simplified traditions of jazz were able to garner for a while. MINGUS: None of you has dealt with another aspect of this. This talk of small, select audiences will just continue the brainwashing of jazz musicians. I think of Cecil Taylor, who is a great musician. He told me one time, "Charlie, I don't want to make any money. I don't expect to. I'm an artist." Who told people that artists aren't supposed to feed their families beans and greens? I mean, just because somebody didn't make money hundreds of years ago because he was an artist doesn't mean that a musician should not be able to make money to day and still be an artist. Sure, when you sell yourself as a whore in your music you can make a lot of money. But there are some honest ears left out there. If musicians could get some economic power, they could make money and be artists at the same time.

ADDERLEY: No, I don't think so. I think that you can play practically anything so long as your concept is one of bringing it into jazz. We have some Japanese folk music in our repertory which Yusef Lateef has reorganized, and we're working on a suite of Japanese folk themes. GLEASON: There's no limitation to the variety of materials which can be in cluded in jazz without jazz losing its own identity - provided the player is a good jazz musician. We've already had the example of all sorts of Latin and African rhythms brought into jazz. We have bossa nova, which is an amalgam of jazz and Afro-Brazilian music, and we will have others. In fact, I think that the bringing into jazz music of elements of the musical heritage of other cultures is a very good thing, and something that should be encouraged. MINGUS: It's not that easy. Sure, you can pick up on the gimmick things. But I don't think they can take the true essence of the folk music they borrow from, add to it, and then say it's sincere. I'm skeptical, because what they probably borrow are the simple things they hear on top. Like the first thing a guy will borrow from Max Roach is a particular rhythmic device, but that's not what Max Roach is saying from his heart. His heart plays another pulse. What I'm trying to say is that you can bring in all these folk elements, but I think it's going to sound affected. BRUBECK: I don't agree that it necessanly has to sound that way. This is something that has concerned me for a long time. About 15 years ago, I wrote an article for Down Beat - the first article I ever did - and I said jazz was like a sponge. It would absorb the music of the world. And I've been working in this area. In 1958, I did an album, Jazz Impressions of Eurasia, in which I used Indian music, Middle Eastern music, and music influenced by certain countries in Europe. I certainly think jazz will become a universal musical language. It's the, only music that has that capability, because it is so close to the folk music of the world - the folk music of any country. RUSSELL: I still have my doubts about this approach. When I say I think jazz can become a universal kind of music, I mean it in the sense of pure classical music. I don't mean by consciously melting the music of one culture with an other. I mean that jazz through its own kind of melodic and harmonic and rhythmic growth will become a universal music. Furthermore, I find that American folk music in itself is rich enough to be utilized in terms of this new way of thinking. But as for going into Indian or Near Eastern cultures, it's not necessary for me. Oh, I can see its value as a hypnotic device - you know, inducing a sort of hypnotic effect upon an audience. But many times that doesn't really measure up musically. It doesn't produce a music of lasting universal value. And I think jazz is capable of producing a music that is as universal and as artistic as Bach's. GILLESPIE: I'm with Ralph Gleason on this. So long as you have a creative jazz musician doing the incorporating of other cultures, it can work. Jazz is so robust and has such boundless energy that it can completely absorb many different cultures, and what will come out will be jazz.

GILLESPIE: The prediction may be true, but as of now, jazz is still inherently American. It comes out of an American experience. It's possible that jazzmen of other cultures can use jazz through a vicarious knowledge of its roots here or maybe they can improvise their native themes and their own emotional experiences in the context of jazz. It's also possible that one day American jazz will become really, fundamentally, international. In fact, I think that the cultural integration of all national art forms is inevitable for the future. And when that happens, a new type of jazz will emerge. But it hasn't happened yet. KENTON: I think it's altogether possible. And it would be very good for the American ego if an outstanding player did come from left field somewhere. ADDERLEY: I don't think there ever will be an important, serious jazz musician from anywhere but the United States, if only because jazz musicians themselves are not going to allow jazz to escape from where it was developed. I'm talking about real jazz. SCHULLER: No, I don't agree. It's not at all inconceivable that in the next five or ten years, an innovator could come from Europe. Of course, it depends on where you choose to draw your limitations as to what jazz is. If you mean Cannonball's kind of jazz, which is certainly in the main stream of jazz development, then I'd agree with you. But jazz can no longer be defined in only that way. Jazz has grown in such a way as to include what even ten years ago would have been considered outside of jazz or very much on its periphery. The music has grown to such an extent that these things are now part of the world of jazz; and as jazz reaches out and expands and goes farther into these outer areas, jazz will of necessity include players who do not have this main stream kind of orientation. So that, in this larger sense - and I know this is the sense in which John Lewis' statement is to be taken - it's entirely possible to have important innovations come from outside this country. A genius can crop up anywhere. RUSSELL: Perhaps, but there has not been a precedent yet for any major contributor coming from any but our country, or more specifically, from any other city but New York. I mean, he's had to have worked in New York at one time or another. I suppose the reason for the importance of New York is the interchange that goes on among musicians in this city, even when they're not in contact. Also, there's a feeling of panic and urgency in New York which provides the trial by fire that seems to make it happen. In New York, you always get a nucleus of people who haven't settled into a formula, who haven't yet sold out for comfort or for other reasons. The nucleus of that kind of musician seems to gather here, and they inspire one another. MULLIGAN: There's a catch in the question. When you say important innovation," that implies something different from talking about a great player who will be influential on his instrument. After all, guys have already come out of other countries who have influenced people here. Django Reinhardt is a perfect example. As Gunther says, there's no telling where genius is going to come from. But whether any major innovations in jazz are going to come from abroad - something which will radically change what went before - George is probably right, though I don't know about the New York part of what he says. What seems important to me - and I've noticed this often - is that the biggest problem jazz musicians from other countries have is that they have grown up in an entirely different kind of musical background. Most of us in this country are raised with not only jazz, but all the popular music of what ever particular time we're growing up in. But foreign players don't have that kind of ingrown background. Yet, it's also a little more complicated than that. The reason I wouldn't be surprised to see great players coming out of other countries, and conceivably creating something different on their instruments, is that fellows who don't speak English wind up phrasing differ ently. Many times, I hear players who speak Swedish or French imitate the phrasing of an American jazz player, but it's not quite right, because the very phrasing of an American jazz player reflects his mode of speech, the accent of his language, even his regional accents. Perhaps, when foreign horn men begin reflecting their natural phrasing, we will get significantly different approaches. KENTON: What we have to remember is that while it's true that a foreign player has to be exposed to American jazz be fore he can grasp the dimension and the character of the music, that doesn't mean he can't eventually contribute without even visiting the States. American jazz musicians now are traveling so much around the world that foreign players can stay at home and be exposed to enough American jazz so that they can become part of the music. MINGUS: I don't see it that way. Not the way the world and this country is now. Jazz is still an ethnic music, fundamentally. Duke Ellington used to explain that this was a Negro music. He told that to me and Max Roach, as a matter of fact, and we felt good. When the society is straight, when people really are integrated, when they feel integrated, maybe you can have innovations coming from someplace else. But as of now, jazz is still our music, and we're still the ones who make the major changes in it.

GILLESPIE: Well, mine was the first band that the State Department sent in an ambassadorial role, and I have no doubts that jazz can be an enormous political plus. When a jazz group goes abroad to entertain, it represents a culture and creates an atmosphere for pleasure, asking nothing in return but attentiveness, appreciation and acceptance - with no strings attached. Obviously, this has to be a political advantage. GLEASON: I'm in favor of sending more jazz musicians overseas everywhere. Now, whether this turns out to be a political gain or not, I don't know. I do think it's a humanitarian and an artistic gain. I don't think we are totally conning our selves as the United States of America when we consider the enthusiastic reception of a jazz unit in a foreign country to be a political plus. As Tony Lopes, the president of the Hong Kong Jazz Club, remarked recently, "You can't be anti- American and like jazz." But I don't think that any amount of jazz exported to Portugal, for instance, will ever make the attitude of the American Government toward the government of Portugal accepted by the Portuguese people as a good thing. Same thing for Spain and the rest of the world. But no one has yet seen a sign: AMERICAN JAZZMAN, GO HOME! ADDERLEY: Sure, I think having a jazz musician travel under the auspices of the State Department is a good thing. It can signify to the audience for which it is intended that the United States Government thinks that jazz is our thing, we re happy with it, and we want you to hear some of it because we think it's beautiful. RUSSELL: But there's an element of hypocrisy there. The very people who send jazz overseas are not really fans of jazz, and the country in whose name jazz is traveling as an "ambassador" completely ignores its own art form at home. It's not going to hurt the musician who goes, however, because music traditionally is known for its ability to unite at least some of the people. At least, the people in power do recognize the capacity jazz has to unite people. ADDERLEY: Yes, it can unite people, but politically, I don't think jazz does a damn thing. I don't think it influences anybody that way. I think the Benny Goodman tour had nothing to do with helping create a democratic attitude in a Communist country. BRUBECK: There are other kinds of political effects. I certainly think that when the Moiseyev Dancers were here, there was kind of a friendship toward Russia which was communicated through almost every TV set tuned to those people. The effect was like saying, "Well, the Russians can't be too bad if they've got great, happy people like these dancers, singers and entertainers. They must be very much like us. In fact, they might be better dancers." And communication from jazz groups going overseas is the same thing in reverse. After all, when we were in India during the Little Rock crisis, it made the headlines in the Indian newspapers seem maybe not quite so believable to an Indian audience that had just seen us. Our group was integrated, and the headlines were making it sound as if integration was impossible in the United States. But right before their eyes, they saw four Americans who seemed to have no problems on that score. And I think there are other assets as well. SCHULLER: I was able to get an idea of the impact of jazz in Poland and Yugouslavia a few months ago. It's hard for anyone who hasn't been there to realize the extent to which people abroad, especially in Iron Curtain countries now, admire jazz and what it stands for. I mean the freedom and individuality it represents. However, in many cases, they don't even think of it as a particularly American product. They regard it simply as the music of the young or the music of freedom. One thing that does concern me about ,sending jazz overseas is the occasional lack of care in selecting the musicians who go. The countries where many of these musicians have been sent have been much more hip than our State Department. MINGUS: I wish the Government was more hip at home. They send jazz all over the world as an art, but why doesn't the Government give us employment here? Why don't they subsidize jazz the way Russia has subsidized its native arts? As I said before, rather than go on a State Department tour overseas, I'd prefer to play for people here. The working people. The kids.

KENTON: I feel the same way about the word jazz as some other musicians do. The word has been abused. I think it was Duke Ellington who said a couple of years ago that we should do away with the word completely, but if you do, another word will take its place. I don't think the situation would be changed at all. BRUBECK: Yes, Duke has spoken of dropping the word jazz. I agree with him.Just call it contemporary American music, and I'd be very happy. But if you keep calling it jazz, it doesn't make me unhappy. ADDERLEY: The word doesn't bug me in the least. In fact, I'm very happy to associate myself with the term, because I think it has a very definite meaning to most people. It means something different, something unique. Furthermore, I like to be identified with all that Jazz represents. All the evil and all the good. All the drinking, loose women, the narcotics, everything they like to drop on us. Why? Because when I get before people, I talk to them and they get to know how I feel about life and they can ascertain that there is some warmth or maybe some morality in the music that they never knew existed. RUSSELL: The term isn't at all burden some to me. I like to accept the challenge of what "jazz" means in terms of the language we inherited and in terms of trying to broaden it. The word and what it connotes play a part in my musical thinking. It forces me sometimes to restrict an idea so that it will come out with more rhythmic vitality. In other words, occasionally I'll sacrifice tonal beauty for rhythmic vitality. GLEASON: Once again, I'm not sure what the question means. In one sense, jazz covers the whole spectrum of popular music in the country. There are aspects of jazz in rhythm and blues, rock 'n' roll, Van Alexander's dance band, the Three Suns. So I don't know whether it can expand too far or not. Everybody means what he means when he says jazz. He doesn't always mean what you or I mean. And I don't think there's any reason to sit around looking for a new word, because we're not going to invent a new word. When the time comes - if it ever does - for a new word, it will arrive. Down Beat conducted a rather silly contest some years ago to select a new word for jazz, and came up with "crew- cut." That word had a vogue which lasted for precisely one issue of Down Beat. MINGUS: Well, the word jazz bothers me. It bothers me because, as long as I've been publicly identified with it, I've made less money and had more trouble than when I wasn't. Years ago, I had a very good job in California writing for Dinah Washington and several blues singers, and I also had a lot of record dates. Then by some chance I got a write-up in a "jazz" magazine, and my name got into one of those "jazz" books. As I started watching my "jazz" reputation grow, my pocketbook got emptier. I got more write-ups and came to New York to stay. So I was really in "jazz," and I found it carries you anywhere from a nut house to poverty. And the people think you're making it because you get write-ups. And you sit and starve and try to be independent of the crooked managers and agencies. You try to make it by yourself. No, I don't get any good feeling from the word jazz.

KENTON: Well, I don't know as we've ever had a great raft of jazz singers. There have been singers who border on jazz and whose styles have a jazz flavor, but there haven't been many out-and-out jazz singers. I mean somebody like Billie Holiday who was 100 percent jazz. You could even hear it in her speaking voice. No, I don't think we're any shorter of that kind of jazz singer than we were 20 years ago. GLEASON: Agreed. There has always been a scarcity of significant jazz singers. And there will always be an important place for singing in jazz. I don't see any changes, however, that we're likely to have in the concept of jazz singing. The things that were done by Ran Blake and Jeanne Lee seem to me to have almost nothing to do with the possibilities of expanding the scope of jazz singing. Carmen McRae is the best jazz singer alive today and what she's doing is really simple, in one sense. And because of that simplicity, it's exquisitely difficult. ADDERLEY: The question is a hard one for me, because I don't know just what a jazz singer is. What does the term mean? We've had our Billie Holidays, Ella Fitzgeralds, and Mildred Baileys and Sarah Vaughans, but they've been largely jazz oriented and jazz associated. Any real creative jazz innovation has been done by an instrumentalist. In other words, to me jazz is instrumental music, so that, although I'll go along with a term like jazz oriented, I don't recognize a jazz singer as such. MULLIGAN: I agree with that. I've always thought of jazz as instrumental music. To be sure, there have been singers who were influenced by the horn players - and a lot of them wound up being excellent singers who learned things about phrasing that they would never have learned otherwise. But fundamentally, the whole thing of improvising with a rhythm on a song, or improvising on a progression, is instrumental. It always bugs me when I hear singers trying to do the same things the horns do. The voice is so much more flexible than the horn, it seems unnecessary for a singer to try to restrict himself and make himself as rigid in his motion as a horn. To answer the question, I'd say singers do have a function in jazz, but as Cannonball says, it's more accurate to refer to them as jazz-oriented singers. RUSSELL: I agree that superior jazz singers are rare, but I think it's possible - as in the case of Sheila Jordan - for a good vocal improviser to give you the same experience you get from listening to instrumental jazz. I mean a singer who is musical enough to take a song and make his or her own composition out of it. SCHULLER: It's a difficult subject - jazz singing. I don't think there ever were any criteria for jazz singing. If you look at the few great jazz singers, you'll find they made their own criteria, but those criteria couldn't be valid for anybody else, because they were too individual. What Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughan - especially the early Sarah Vaughan - did was so individual it couldn't be used by anyone else. There's another problem here, too. A matter of economics. Singers with jazz capacity are usually drawn toward the big-money market that exists on the periphery of jazz. Often it's simply a matter of survival, because it's economically very difficult for a singer to survive in jazz. So they move to the periphery and their work becomes diluted. I've said this before, and I can't say it often enough, that so many people are worried about the possible dilution of jazz through third-stream music, but no one seems to be concerned about the constant, daily, minute-by-minute dilution of jazz by the commercial elements in our music industry.

GILLESPIE: Improvisation is the meat of jazz. Rhythm is the bone. The jazz composer's ideas have always come from the instrumentalist. And a lot of the things the composer hears the instrumentalist play cannot be notated. I don't think there'll ever he a situation in which all of jazz will he written down with no room for the individual improviser. GLEASON: If Bill Russo has suggested that a time may come when all jazz is notated with no room left for the improviser, I think he's out of his mind. This is not foreseeable. There will always he guys playing jazz who can't read music. There will always be guys playing jazz who just want to improvise, and don't want to read and yet who can read. And there may be a great deal of jazz composed in the future that will be played and well played, and good jazz. But it will not be exclusively compositional jazz. Improvisation, and the quality and feeling of improvisation - or the implication of improvisation - seem to me to be characteristic of good jazz, and I think always will be. KENTON: Both composition and improvisation will continue to be important to jazz. The problem today is that good improvisers are so rare. There are many people who can make sense out of their improvisations, but very few people are really saying anything. SCHULLER: I do think it's possible to have jazz which is totally notated, but I would deplore the possibility of eventually eliminating improvisation from jazz. Improvisation is the fundamental and vital element which makes jazz different from other music. Taking improvisation away from jazz is almost inconceivable. RUSSELL: I don't think the question takes into account what is really happening in terms of jazz composition. Notation in the old sense is becoming less important. I think the jazz composer's role will not necessarily be that of notating the music, but of designing situations, blueprinting them - and then leaving it to the improviser to make the blue prints come alive. But this won't be happening in terms of actual musical notation as we've known it. As Dizzy says, some ideas just can't be notated. I know that Ornette Coleman thinks the music of the future is going to be entirely improvised. I don't think that's necessarily true either, but I think there is a middle ground.

GLEASON: The fun hasn't gone out of jazz for me, baby. And when it does, you won't find me sitting around in night clubs or concerts listening to jazz musicians. And I don't think the fun has gone out of jazz for Miles Davis, no matter how much he may complain, nor for Dizzy Gillespie, nor for anybody else who is really playing anything worth listening to. The fun certainly hasn't gone out of jazz for Duke Ellington or even Louis Armstrong. And what do you mean "the happy sound"? The happy sound is still here. Listen to Basie. Listen to Miles Davis playing Stella by Starlight or Walkin'. Happy sound? John Coltrane's My Favorite Things is a happy record, a beautiful record. The happy sound is never going to go out of jazz. Jazz expresses a variety of emotions, all kinds of moods, and not exclusively one emotion any more than exclusively one style or one rhythm section, or one anything else. I don't think jazz has become too solemn. I think some of it has becomeboring, but I don't think all of it has. KENTON: Yes, but so much of the jazz heard today is full of negative emotions and ugly feelings. I, for one, wish the happy sound would return. Its absence is one of the things that have killed jazz commercially. People don't want to subject themselves to these terrible experiences. After all, jazz shouldn't be an education. It's a thing you should enjoy. If you have to fight it, I don't think the music's any good. BRUBECK: I think we ought to look at this historically. To some extent, jazz was a music of protest when it began. It expressed the feeling of Negroes that they must achieve freedom. And at other times in the history of jazz, the music has again been used as a form of protest. That's the way it's being used by some today. But jazz isn't only a music of protest. It was and is also a music of great joy. Let's bring the joy back into jazz. Jazz should express all the emotions of all men. GILLESPIE: It seems to me that the answer is simple. Today's jazz, yesterday's jazz, tomorrow's jazz - they all are based on all of the component parts of human experience. An artist can be comic and satirical and still be just as serious about his music as an artist who is always somberor tragic. In any case, the members of an audience seek out those artists who fill their particular needs - whether beauty, hilarious comedy, irony or pathos. It's always been that way. Furthermore, moods change from day to day, so that a listener may find one of his needs being met by a particular artist one night and a quite different need being fulfilled by a quite different artist the next night. RUSSELL: As Dizzy says, a satirist can be very serious about his music. And I find a good deal of wit and satire in what's called the "new thing" in jazz. It all depends on what level your own wit is. Some people who think the fun has gone out of jazz simply don't have the capacity to appreciate a more profound level of humor. Now, if jazz is becoming an art music, you have to expect it to search for deeper emotions and meanings in all categories. To me, jazz has never been more expressive on every level than it is getting to he now, and it certainly doesn't lack wit. MINGUS: Now look, when the world is happy and there's something to be happy about, I'll cut everybody playing happy. But as it is now, I'll play what's happening. And anybody who wants to escape what's really going on and wants to play happy, Uncle Tom music, is not being honest. I'll tell you something else. The old-timers didn't think jazz was just a happy music. I was discussing this with Henry "Red" Allen recently, and he told me he doesn't play happiness. He plays what he feels. So do I. I'm not all that happy. SCHULLER: How can anyone expect this music to he happy, or any music to be entirely happy, in these ridiculously un happy times in which we live. I mean, one has to manufacture one's own hap piness, almost, in order to survive. And the music cannot help but reflect the time in which we live. Besides, as jazz changes from an entertainment music to an art music, it will lose a lot of that superficially happy quality it used to have, because if you're entertaining, your job is to make people happy. Some times I'm sorry about this change, but you just can't turn back the clock. I like to listen to happy jazz. Sometimes, I hear good Dixieland and I think, "It's true. That was a happy music. it was fun and there weren't all these psychological overtones and undertones." But what can you do about it? Many of the musicians in jazz today do not live in this kind of happy-go-lucky situation. They don't live that way and they don't feel that way. MULLIGAN: Nonetheless, I do think those who lament the passing of the "happy sound" do have a legitimate complaint. Playing music is fun. That's not to say that everything is necessarily humorous. But humor is not the only thing that's lacking these days. There are a lot of guys who appear to take themselves too seriously. They're too deadly serious about their music. It's one thing to be deeply involved in what you're doing, but it's not necessary to have that terrible striving feeling about art - with capital letters. I find this very disheartening when it happens. It's as a result of self-consciousness that a lot of the fun goes out of jazz.

RUSSELL: Well, the last refuge of the untalented is the avant-garde. Yes, there certainly are musicians who jump on the band wagon - like a few critics. There are musicians who say, "Since there's freedom, we can do anything and make a buck at it, too." But as the standards of the new jazz become clearer and more substantial, these people will be weeded out. They can't possibly survive. GILLESPIE: It all depends on who's doing it. If a man really has something to say, the devices themselves aren't important. It's what comes out. MINGUS: Yes, anything can be used honestly and anything can be used dishonestly. Like, if a man is writing or playing, he's entitled to put a couple of cuspidors in there if that's the sound he hears. But this isn't new. Duke Ellington has used playing cards to rip across the piano strings. He's used clothespins and he's had his trombonists use toilet plungers. GLEASON: When you have experimentally minded musicians, you're going to have experimental music of all kinds. And I don't see anything being done in jazz today that I've heard in person or on records that can be described as Dada in a pejorative sense. I don't think that jazz musicians have reached the point where they have no desire to commuincate. I don't think any artist that I've ever heard of has reached that point. It may be that the terms they select in which to communicate, the vehicles that they use, and the devices that they use, and the language, may, by definition, limit the potential auditors for their communications. But they still want to communicate. KENTON: I don't know whether they don't have any desire to communicate or whether they're just desperate for ideas to such an extent that they're going to try any sort of thing inorder to gain attention. I do think that if this stuff is allowed to go on too long, it's going to ruin the interest in jazz altogether. SCHULLER: My concern with the sort of thing you describe is that it takes away and makes unnecessary most of the fundamental artistic disciplines. I don't even mean specific musical disciplines. I'm putting it on a broader, more fundamental level than that. I mean the old challenge of a seemingly insurmountable object which makes you rise above your normal situation to overcome. In the music of John Cage and some of Stockhausen - and Don Ellis, in so far as he uses a similar approach - this critical element which has been at the base of art for centuries is eliminated. In fact, some of them walit to eliminate the personality of the player. They want to make music in which the Beethoven concept of the creative individual is totally eliminated and the music is instigated by someone, but not created by him. They talk about finding pure chance - which is really a mathematical abstraction which cannot he found by habit-prone human beings - and they try to involve as much chance as is possible in a given situation so as to eliminate this question of the individual personality. This to me is a radically new way of looking at art. It completely overthrows any previous conceptions of what art is, or has been, and at this point, I stop short.

BRUBECK: Well, early in my career, I

realized that I could reach the audience with one thing only, and

that was music. This is something it seems most groups have

forgotten - that the primary reason they are there is to reach

the audience through the music. And I was so aware that I could

reach an audience that way I made it almost a rule to never speak

over the microphone. This lasted for years. We didn't dress in

any way that was beyond the average business suit, and we didn't

wear funny hats or goatees or beards or berets. In other words,

we just let the music do what the music should do - and that is

get to an audience. GLEASON: I don't think the cult of personality holds too great a sway over the world of jazz. Dave has made it big in jazz, for instance, and aside from what he's already said, if you apply the cult of personality to Dave, you've got a guy who doesn't drink or smoke, who has been married to one woman for over 23 or 24 years, and has a houseful of children, likes horses, and wants to stay home in the country. I don't think Dizzy is droll, by the way. I think he is wildly hilarious. And I don't think Miles is aggressively distant, either. And I don't think Mingus is aggressive. And I don't find Louis comical, any more than I find Miles aggressively distant. I think if you look at Louis and have a comic image in your miud, you're doing the man a great injustice. And I also think you're indicating something about yourself. The cult of the personality doesn't seem to me to have any- thing to do with jazz musicians at all, and if it exists, it only has something to do with the jazz audience. ADDERLEY: It depends on what you mean by personality. Some people - Yusef Lateef, Mingus, Dizzy - have strong personalities which they are able to project. They play at people. Yusef, for instance, plays through the horn, not just into the horn. People who don't have this, who cannot project, will never be successful even if they play beautifully. For example, as a group, the Benny Golson - Art Farmer Jazztet lacked a strong enough personality, and it failed. The Modern Jazz Quartet has several strong personalities. They even go in different directions. Everybody in that group is strong, and the group's collective identity is also strong. Dave Brubeck has a strong personality in the sense that he has a definite identity. It's not a wishy-washy kind of thing. MULLIGAN: Any public performer has to have a strong personality to be unusually successful. There are more things possible for somebody who is accepted as a personality, aside from being a musician, than there are for the straight musician who doesn't project. SCHULLER: Yet I would suspect that those who didn't make it to the top in the sense of a fairly broad acceptance must have had something missing beyond just the matter of personality. MULLIGAN: Yes, if a man can blow, it doesn't matter if he's old, if he's blue, or if he's got a personality. As long as people like him. If he can blow. SCHULLER: What I mean is that the matter of coming on with a fantastic getup or a goatee or other "quirks" of personality are all in the realm of fandom. But the more serious listeners to jazz, after all, are very sensitive to the subtle degrees of projection which a player has or doesn't have. A man can be a very fine musician, but there can be a certain kind of depressing or negative quality in his music that will hold him back in terms of acceptance. It may be that you can't fault his music in any way technically, but it doesn't have this way of going out there into the 20th row. And if that's the case, then I think there's nothing terribly wrong in the fact that such a man does not become the star that, say, Charlie Parker was. MINGUS: You're underestimating the fact that jazz is still treated by most people as if it were show business. The question has some validity. Take Thelonious Monk. His music is pretty solid most of the time, but because of what's been written about him, he's one of those people who'd get through even if he played the worst piano in the world. Stories go with musicians, and that again is the fault of the critics - and of the jazz audience, too. There are many ways of being successful. Like going to Bellevue. After I went there on my own, and the news got out, I drew more people. In fact, I even used to bounce people out of the clubs to get a little more attention, because I used to think that if you didn't get a write-up, you wouldn't attract as many people as you would with a lot of publicity. But now I see what harm that kind of write-up has done to me, and I'm trying to undo it. GILLESPIE: I don't know about this cult-of- personality thing. A musician must be who and what he is. If his personality is singular, and if he lets it come through his art naturally, he'll reach an audience. But I don't think you can force it.

GLEASON: As far as I'm concerned, there's a place for jazz on TV, because I'm involved with doing a jazz show on television. It's on educational television, so we aren't hung up with commercials, we aren't hung up with having to play somebody's tune or allowing somebody to sit in with the group. And we aren't hung up with all the restrictions of commercial television as to length and selection of material. We have a multimillion-viewer audience, and the musicians do whatever they want to. In fact, the musical director of each one of the programs on Jazz Casual is the leader who's on the program that week. He selects the music. Sometimes he lets us know in advance what it will be and sometimes we find out when he plays it. And I don't think jazz' attraction is specialized. Let's just say all jazz programs in the past have been failures - I'll buy that - with the exception of the one show they did on Miles Davis, and that CBS show, The Sound of Jazz.

GLEASON: With the exception of those (and Jazz Casual), almost everything I've seen on television on jazz has been a failure. And the reason for it is that television has never been willing to accept the music on its own terms, but always wanted to adapt the music to television's requirements. Under the assumption that you had to produce a product that was palatable to some guy walking down the streets of Laredo, I guess, I don't know. Jazz will get along on television if they'll leave jazz musi cians alone, and let them play naturally. GILLESPIE: Exactly. TV, of all media, is ideally suited to the uniqueness of jazz, because you can hear and see it while it's being created. I think the big mistake in most of the jazz formats in the past has been their lack of spontaneity. Maybe jazz could be done on TV by means of a candid-camera technique. KENTON: If you're talking about the major networks, I'd say there's no place on television for jazz at this time at all, because television has to appeal to the masses, and jazz has no part of appealing to the masses. It's not a case of how well it's presented - whether by candid camera or some other device. It's 'just that jazz is a minority music, it appeals to a minority, and that minority is not large enough to support any part of commercial television. RUSSELL: I'm almost as pessimistic. It won't happen so long as the tyranny of the majority is working. No producer in his right mind is going to have the courage to buck the majority and come up with something tasteful. Yet, if one of the powers in the industry did have enough courage to put on something very taste fully conceived, and if he did it often enough, I think jazz would eventually get through. ADDERLEY: Well, so far all of you have been talking about jazz as a separate thing on television. I don't really see why jazz has to be shunted off to be a thing alone. I don't see why it's not possible to present Dave Brubeck as Dave Brubeck, jazz musician, on the same program with Della Reese. We in the community of jazz seem to feel that we need our own little corner because we have something different that is superior to anything else that's going. But it's all relative,and there's a kind of pomposity involved in that kind of attitude when you check it. I think that I could very easily be a guest artist on the Ed Sullivan show or the Tonight show along with the other people they have. Like Allan Sherman. Let me do my thing, and there's a good chance I might communicate to the same mass audience that he does. The same thing is true of Miles Davis or Dizzy or any. one else. I think there's a place for us on television - once we get admitted to the circle. MULLIGAN: I still think it would be possible to produce a reasonably popular jazz show, but it would have to start on a small scale. I think a musician - whether it's me or whoever - should be master of ceremonies if the show is going to have the aura of jazz. And this musician would have to be able to produce a musical show with enough variety to be able to sustain itself. If I were doing it, and I'd like nothing better than to try, I'd prefer to do it as a local show which could be taped for possible use on networks. That way we could keep expenses down while we tried to prove what kind of audience we could attract. Now, Cannonball talks about being part of the circle of guest attractions on the major shows. Well, our group has been on some of them, and I don't know whether it really does us any good or not. Being on that kind of show does give you a kind of prestige value with people who have no awareness of jazz. But I wonder whether seeing and hearing jazz groups in that sort of surrounding gives TV viewers any increased sensitivity to jazz. I think not. It just makes them think of me - or any of the other jazz musicians who make those shows - as being bigger names, as being bigger stars in relation to stars as they think of them. But it doesn't really help create a larger audience for jazz itself. I'll keep on doing those appearances as long as they're offered to me, but what I'd really like to try is that local show. I think we could build a really good presentation which people would go for. But nobody's made an offer yet. MINGUS: Let's face it. Television is Jim Crow. Oh, for background scores, the white arrangers steal from the latest jazz records. But as for putting our music on television in our own way and having us play it, no. Not until the whole thing, the whole society changes.