|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

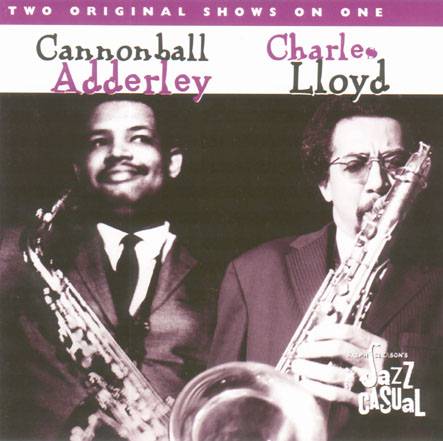

"JAZZ CASUAL" |

![]()

|

Cannonball Adderley Alto sax

Nat Adderley Tp

Joe Zawinul Piano

Sam Jones Bass

Louis Hayes Drums

|

Recorded for the Jazz Casual TV show , October 24 1961 |

-

Scoth & Water 4:58 (Joe Zawinul)

-

Interview 5:33

-

Arriving Soon 8:32 (Eddie Vinson)

-

Interview 0:39

-

Unit Seven 6:44 (Sam Jones)

-

Commentary by Ralph Gleason 0:56

-

unit Seven (continued to fade) 1:22

Track 8-9-10 By Charles Llyod Quartet ( June 18 ,1968)

|

In the sixties, jazz musicians increasingly found themselves in a battle for listeners' attention. It was a battle they often lost.

This was especially true toward the end of the decade, as first the advent of the Beatles and then the birth of psychedelia gave rock & roll a cachet it had never before enjoyed. Not only did rock continue to outsell jazz; vast numbers of young people now looked to rock stars rather than jazz musicians for the latest word on what was hip and cutting edge. But there were some jazz musicians who knew how to break through the indifference and even hostility that separated their peers from widespread acceptance, without having to make artistic compromises. Critics and fellow musicians often accused them of selling out, but a more charitable (and accurate) way to put it is that they had found a way to play music that was both satisfying to them and accessible to people who didn't normally listen to jazz. The extraordinary saxophonist bandleaders represented here are two of the more noteworthy examples. Alto saxophonist Julian "Cannonball" Adderley (1928-75) discovered his personal formula for reaching listeners early in his career. His playing was always both sophisticated and earthy, but he quickly learned that emphasizing its earthy side was the best way to grab an audience's ears and hold on to them. (Once he had hooked them with the down-home blues, it was easier to get them to sit still for the more challenging material that was always part of his repertoire.) Adderley also happened to be a naturally warm and articulate man, and he had a rapport with audiences that tended to put them at ease and make them more receptive to his musical message. Tenor saxophonist and flutist Charles Lloyd (born in 1938) passed through Adderley's sextet on the way to establishing himself as a bandleader in his own right, but his approach to reaching an audience had little in common with that of his onetime boss. Although he was capable of playing the blues with as much authentic feeling as Adderley (Lloyd's Memphis roots were not all that far from Adderley's Florida ones), his muse led him in a much more abstract, exploratory direction. And where Adderley's friendly between-songs patter was one key to his success, Lloyd preferred to exude an air of mystery - and, at the height of his success in the middle and late sixties, didn't talk to his audiences at all. Adderley the down-home bluesman and Adderley the great communicator are both on display here. His quintet's three selections are all variations on the basic 12-bar blues format, and his interview segment with Ralph J. Gleason is entirely devoted to a discussion of that format- how it has evolved over the years, how Adderley approaches it, the various ways in which the quintet's numbers are different from the traditional blues. As Gleason observes, Adderley's years as schoolteacher stood him in good stead; he explains some fairly complicated ideas about musical structure in a very clear and entertaining way. But of course the main attraction here is Adderley's playing-and that too is both clear and entertaining. The remarkable variety of cries, whoops and wails he could coax from his alto saxophone added up to one of the most personal sounds in jazz, and one of the most emotionally moving as well. Jazz just doesn't get any more soulful than his brief but powerful out-of-tempo introduction to "Arriving Soon.") It's not surprising that Adderley was one of a handful of musicians who remained a favorite of urban black audiences long after they had otherwise lost interest in jazz. Charles Lloyd, on the other hand, owed much of his success to a most unlikely source of support. the rock audience. Lloyd's music was in some ways not far removed from the outer fringes of the jazz avant-garde. A performance like "Tagore," which begins with Keith Jarrett strumming the strings of the piano and evolves into a freewheeling saxophone duet between Lloyd on tenor and Jarrett on soprano, was pretty heady stuff for any audience in 1968. But Lloyd also loved simple melodies and basic rhythms-the section of "Tagore" on which he plays flute, accompanied only by Jack De Johnette's drums, is a good example of that-and he found a way to combine the simple and the complex (and own unusual but potent charisma) into a mixture that spoke to the bussed-out crowds at the Fillmore Auditorium at least as loudly as it did to the more knowledgeable jazz aficionado. Coincidentally or not, the pianists in both these groups would go on to be among the most important Jazz musicians of the seventies-and, like their former employers, to achieve fame beyond the confines of the jazz world. Joe Zawinul had only recently joined the Adderley quintet at the time of this performance in 1961, but he had already contributed the sprightly "Scotch and Water" to its book. He subsequently wrote some of the group's biggest hits, including "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy," its only Top 20 single and one of the first jazz records to feature an electric piano. After leaving Adderley in the late sixties, he became more deeply involved in electronics and worked with Miles Davis (who recorded a number of his compositions, notably "In a Silent Way") before co-founding the influential fusion group Weather Report with saxophonist Wayne Shorter. Following his tenure with the Charles Lloyd Quartet, Keith Jarrett too worked with Miles Davis (as did Jack De Johnette). He played electric keyboards during his brief stint with Davis but thereafter defied the electric-jazz trend by devoting his energy to the grand piano, and achieving worldwide success with a series of unaccompanied solo albums. The contrast between Jarrett's musical philosophy and Zawinul's is even more striking than the contrast between Lloyd and Adderley, but all four of these musicians have at least one thing in common: They proved that it's possible to get large numbers of people to listen to you by playing exactly what you want to play. Notes by Peter Keepnews

|