|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

"PORGY AND BESSS" |

![]()

|

A rare picture sleeve 45 rpm from U.K.

|

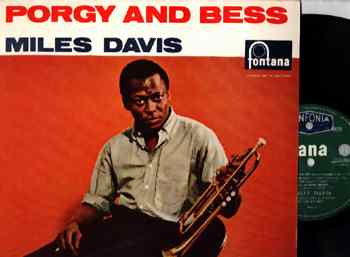

10 inches French issue (out of stock at CD NOW !!!!!!!!!!)

Personnel

Miles Davis-Trumpet and Flugelhorn

Trumpet: Louis R. Mucci, Ernie Royal ,John Coles ,Bernie Glow

Trombone: Jimmy Cleveland ,Joseph Bennett ,Richard Hixon ,John ("Bill") Barber

Saxophone: Julian E. Adderley ,Daniel B. Banks

Frenchg horns: Willie Ruff, Julius Watkins, Gunter Schuller

Flutes: Philip Bodner , Romeo M.Penque

Tuba :John "Bill" Barber

Bass: Paul Chambers

Drums: Philly Joe Jones

The Buzzard Song

Bess, You Is My Woman Now

Gone

Gone, Gone, Gone

Summertime

Bess, Oh Where's My Bess

Prayer (Oh Doctor Jesus)

Fishermen, Strawberry and Devil Crab

My Man's Gone Now

It Ain't Necessarily So

Here Come de Honey Man

I Loves You, Porgy

There's a Boat That's Leaving Soon for New York

|

"The great music of the past," wrote George Gershwin at the time he was working on Porgy And Bess "...has always been built on folk music. This is the strongest source of musical fecundity... Jazz I regard as an American folk music, not the only one but a very beautiful one which is in the blood and feeling of the American people?' It was with particular attention to the blues-jazz inspiration inherent in Porgy And Bess that Miles Davis and Gil Evans approached the vocal score. As they worked out plans for the set-and Miles worked with Gil Evans when it was still at the discussion stage-it occurred to Gil that not only were Miles and he contributing to an interpretation of the score in terms of orchestral jazz but Gershwin himself was creating anew as jazz ideas, always latent in his scores (as well as expressed), came to life. Gil said, "The three of us, it seems to me, collaborated in the album?' In the late 1940s, when Gil Evans and Gerry Mulligan helped Miles set up an historic nine-piece band that played briefly at New York's Royal Roost, the idea of "the new thing" (as some musicians called modern jazz) having more accommodation than that of a "hitch-hike" in a swing band had barely been thought of. Though it was to be almost a decade before Gil Evans became well known to the jazz public, his original approach to jazz orchestration was an immediate sensation amongst musicians. In his more personal work Gil-whose arranging stints with Claude Thornhill had already won him respect-was preoccupied with providing an adequate orchestral setting for the new sounds of Jazz. He did this not merely in introducing new instruments (such as French horns) and adding new colors to the orchestral palette but in freeing modern jazz from big-hand swing that, even when meritorious in its own right, often had a restrictive influence on the projection of the new tonal and rhythmic concepts. This album is not merely a jazz treatment-with Porgy And Bess marking the blast-off area-it is an orchestral approach to the score. Perhaps the most suggestive comparison would be some of Ellington's work. But that by no means tells the whole story. Gil's originality in orchestral jazz and Miles Davis' power ful talent (that is buttressed by an increased grasp of complex musical problems) suggest that when these two collaborate successfully, the wail will be heard 'round the world! Thus, the album involves a distinguished jazz arranger who was largely self-taught, an honored composer who worked as a song-plugger in Tin Pan Alley and a dynamic artist in jazz who wrote Charlie Parker phrases on matchbook covers. And just to fatten it up, there's the lyric writer, brother Ira-the piano in the Gershwin home was meant for him but George was the one who used it-and the "book" about life on Catfish Row by DuBose and Dorothy Heyward. Though there are no vocals in this presentation, these last are important because Miles and Gil do not merely flirt with show music tunes, they do a job on this greatest of operettas related to American black folk music and jazz. In working from the vocal score, Gil was aware of both literary and musical relationships. On "Prayer (Oh Doctor Jesus)" he sensed the seriousness with which Gershwin had approached the theme, and in this "healing" prayer; in which the "amens" etc. are given to the orchestra, there is an urgency, a suppliance of sound. Then there is the use made of "I Got Plenty of Nothin"' as the opening release of "It Ain't Necessarily so" and the evocative strain in "My Man's Gone Now" that sounds almost like a reprise of"Summertime" Porgy And Bess it is generally conceded, represents the culmination of Gershwin's artistry. On "Bess, You Is My Woman Now"-as, indeed, throughout the score-many passages carry the Gershwin signature. One of the great melodic writers of our time, Gershwin's work had both variety and vitality-even in the pop tunes he ground out in the shank of the night, a cigar clamped to his jaw-yet there was usually a distinctiveness, something immediately recognizable in it. The infusion of blues-jazz elements throughout his music made him, from the beginning, immensely popular with jazzmen. Walter Damrosch-in 1925, when "Concerto in F" had its premiere-opined that, in effect, Gershwin had made a lady out of jazz. But the following year, to the arbiters of our cultural mores, she was still a tramp; even "The Etude" which hedged in a painful effort to be fair-minded, discussed "The Jazz Problem;' giving it the solemnity due a momentous moral issue ! However; we are concerned not merely with the young Gershwin whose "Concerto In F" was such a memorable contribution to American music, but with the still younger Gershwin who cut piano rolls in the same shop as James P. Johnson, the old master of Harlem piano, and with the composer who later on listened to Bessie Smith and the blues. At the time the "Rhapsody In Blue" was orchestrated, jazz orchestral writing as we know it today was unheard of. Gershwin himself did not orchestrate it, being unskilled in that sphere, but perhaps this was not so much of a lack as he himself thought at the time. The classically trained men of those days-even those hardy souls who were willing-were quite unable to interpret jazz scores. Jazzmen, on the other hand, were usually incapable of symphonic reading of professional calibre. Nowadays, many men have equal facility in both fields. Yet in the present decade, jazz orchestration remains more than ever a special field. Porhaps this is why it seems to find expression best, as a rule, through its own writers. In a recent conversation, Gil mentioned Miles' beautifully deliberate-controlled, yet suspenseful-rhythmic style on slow tempos, reminding me of Bill Russo's statement (in The New Yearbook of Jazz Horizon) that "the melodic curve, the organic structure, and the continuity of a Miles Davis solo.. .cannot be perceived very easily by a classically trained musician?' But some of the men in this band, such as Gunther Schuller; have had classical training and are examples of what I referred to in a magazine piece as "a new breed of cats?' Though hecan particularize with regard to the innumerable facets of orchestral writing, Gil thinks of the music in its entirety, as a painter thinks of a canvas. Indeed, when he speaks of depth or density of sound, impingement of instrumental tone, the dynamics of structure and the particular require ments of each theme, the resemblance to descriptions of pictorial art is striking. And when one recalls Picasso's dictum that a painting is alive, the parallel is completed. Gil first met Miles when the latter was playing with Charlie Parker on 52nd Street and their respect for each other, often expressed in print, is testified to in the excellence of their collaborative efforts such as Miles Ahead "I think a movement in jazz is begin ning away from the conventional string of chords, and a return to emphasis on melodic rather than harmonic variations;' Miles told Nat Hentoff in a recent interview (The Jazz Review December, 1958). He also made this interesting statement, "When Gil wrote the arrangement of "I Loves You, Porgy;' he only wrote a scale for me to play. No chords. And that other passage with just two chords gives you a lot more freedom and space to hear things?' (In this set, incidentally, the trumpet passages by Miles are usually played with mute, the flugelhorn open.) In these days of stepped-up jazz production, the good things, like the good men, are still a rarity. Especially so are deeply moving performances such as these that seem infused with an inner fire that cannot be simulated. Miles' beauty and variety of tone, his versatile manipulation of horns, is put to excellent use here as he-with the orchestral projections of Gil's arrangements-produces incomparable renderings of Porgy And Bess. In speaking of certain of Miles' solo passages, Gil remarked, "Miles can be hot in the true meaning of the word?' Every piece has its own interest, orchestrally speaking, e.g., the grainy, pungent harmony on "Bess, You Is My Woman Now;' the utilization of brasses, tuba and brooding French horns of "The Buz zard Song?" On the latter one notes how sureness and strength give sinew to the lovely tone of Miles' horn. "Gone" is a holiday for jazzmen, especially for Miles, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, who are gone for several choruses. This is not from the score but relates to "Gone, Gone, Gone;' a beautifully harmonized spiritual, pulsed by a slow; graceful rhythm. As for the previous track, taken at a fast tempo, Gil said, "This is my improvisation of the spiritual. In the middle of it Miles, Paul and Joe improvise on the improvisation!" With a slow chop on drums and a faint swish of cymbals, Miles states the theme of an unusually beautiful "Summertime?' In his solo passages he places tone in rhythm like a painter who uses color knowingly, aware of composition in advance. One of the loveliest Gershwin melodies, "Summertime" is based on a blues motif. It is followed by the lament, "Bess, Oh Where's My Bess" a sweet poignance cradled in rhythm now quiescent, now faster and more agitated in tempo. After "Prayer;", mentioned above, Gil combines "Fishermen" (a song) and the calls of the Strawberry Woman and Devil Crab peddler .Gershwin heard music in street cries and in the matrix of Gil's sensitive background writing. Miles' hauntingly imaginative interpretations are completely devoid of easy artistry. "My Man's Gone Now" is like a tone poem in its evocation of a pathos that gives to commonplace grief a deep and human dignity .On "It Ain't Neces sarily so" horns surround and support Miles in a phenomenal series of choruses. The rhythm, which is very good throughout this demanding set, has an exuberant jazz quality and the manner in which Gil employs short phrases to accent Miles' chorus is in itself masterly. After a sweet interlude-an engaging bit of writing and playing ("Here Comes de Honey Man' ')-there is the superbly played "I Loves You, Porgy?' Then every one has a ball on "There's A Boat That's Leaving Soon For New York?' This is a happy voicing of instruments, using flutes to advantage-the subtle use of instruments throughout this set is fascinating in itself-and as an example of Miles' craftsmanship, note how he feeds the other horns. There are plenty drums, plenty Paul Chambers, plenty everything (The listener need hardly be reminded that this is a band made up of top ranking jazzmen) This bright and happy theme is given a full and exuberant performance, right down to the last drum beat. Porgy And Bess -a folk opera that has humor pathos ,the sweetness of the last bit of honey in the comb and moments of musical greatness- moves like a dance Miles and Gil have given it a superb performance in a new idiom .

Recording Dates 7/22/58: My Man's Gone Now; Gone,Gone, Gone, Gone. No personnel changes. 7/29/58: Here Come Do Honey Man; Boss, You Is ,My Woman Now, It Ain't Necessarily So, Fishermen, Strawberry and Devil Crab . Personnel changes-Jimmy Cobb (drums) replaces Philly Joe Jones 8/4/58: Prayer (Oh Doctor Jesus); Bess, Oh Where's My Boss; The Buzzard Song. Personnel changes-Jerome Richardson (flute) replaces Phil Bodner 8/18/58: Summertime; There's A Boat That's Leaving Soon For New York,I Loves You, Porgy. No personnel changes. Recorded at the Columbia 30th Street Studio in New York City. Produced by Cal Lampley and Teo Macero Digital master prepared by Teo Macero Engineered by Roy Moore Mastered at CBS Studio, Now York, by Vlado Meller |