|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

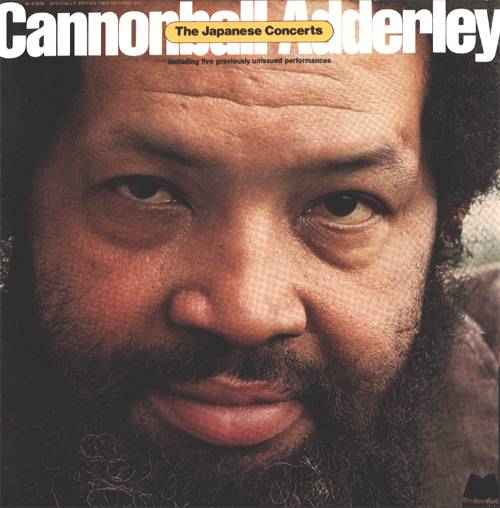

"THE JAPANESE CONCERT" |

![]()

|

|

Julian "Cannonball" Adderley-alto sax

Nat Adderley-cornet

Yusef Lateef-flute, oboe, tenor sax

Joe Zawinul-piano

Sam Jones-bass

Louis Hayes-drums

Side 1:

1. Nippon Soul (Julian

Adderley) Upam Music-BMI 9:32

2. Easy to Love (Cole

Porter) Chappell Music-ASCAP 3:47

3. The Weaver (Yusef Lateef)

Alnur Music-BMI 10:50

Side 2:

1. Tengo Tango (Julian and

Nat Adderley) Upam -BMI 2:37

2. Come Sunday (Duke

Ellington) Tempo Music-ASCAP 7:01

3. Brother John (Yusef

Lateef) Alnur-BMI 13:03

Side 3:

1. Work Song (N. Adderley) Upam-BMI

9:09

2. Autumn Leaves (Prevert-Kosma)

Morley Music-ASCAP/S.D.R.M. 7:27

3. Dizzy's Business (Ernie

Wilkins) Silhouette Music-BMI 6:01

Side 4:

1. Primitivo (J. Adderley)

Elcirro Music-BMI 12:12

2. Jive Samba (Nat Adderley)

Orpheum-BMI 10:37

Recorded during

1963'Japan Tour.

On July 9, in Kosei-nenkin

Hall-"Work Song,""Primitivo," "Dizzy's

Business."

On July 14, in Sankei HalI-"The

Weaver," "Easy to Love," "Autumn

Leaves."

On July 15, in Sankei Hall-"Jive

Samba," "Nippon Soul," "Tengo Tango,"

"Brother John," "Come Sunday."

Sides 1 and 2 originally issued as

Nippon Soul (Riverside 477). Sides 3 and 4 are previously

unissued.

|

Julian Adderley was my friend. He was among the handful of people to whom I felt most closely connected during the almost two decades that I knew him. He was also a musician with whom I worked closely during two specific periods-the very important (to him and to me) six years between 1958 and 1964 that he spent at Riverside Records; and again on two 1975 projects during what turned out to be the last months of his life. None of these facts are, in themselves, exactly unique. I have other friends, including musicians with whom I have spent uncountable quantities of time in the recording studio. More than a few of the musicians I find myself working with now are men I knew and worked with more than a few years ago. Other friends have died, including vastly talented musicians with whom I felt deep ties, like Wes Montgomery and Wynton Kelly. No, none of these facts are unique. But the man was. I first met Cannonbal) some time in 1957. I still remember with reasonable clarity the circumstances of that first meeting .As a matter of fact many of my memories of Cannon are in terms of specifically recalled scenes and incidents. And since-like me and like most of the people I've known in the jazz world-his life seemed in one way or another to be about 90 percent concerned with his music, those recollections and some of the thoughts and comments they stir up can very suitably be presented here. To put it another way: I really find it necessary to write about my friend Julian Adderley, and I can't think of any more appropriate format for that writing than a set of album liner notes. To start with that first meeting: I know it was '57, and I figure it for Spring or Summer-the circumstantial evidence being that I was introduced to Cannon and his brother Nat by Clark Terry (whose own first Riverside album was recorded in April of that year), and that we were all standing around in front of a rather celebrated Greenwich Village jazz club called the Cafe Bohemia. That would seem to indicate a New York night too warm for either musicians or really hip customers to be inside the club between sets: therefore, possibly any time between May and September. Or being outside may just have been a safety measure. The Bohemia, in addition to being celebrated as the place where top bands like Miles Davis's and the Modern Jazz Quartet played when in New York, and as the scene of Cannonball's legendary evening of sitting in with an Oscar Pettiford group when he first hit the big city in 1955, was also well known for a tough owner who shoved customers and musi cians around when they clogged up the narrow bar area. Anyway, there were Cannon and Nat and a midway point in a chain reaction that has always fascinated me (through Alfred Lion of Blue Note Records I first met Thelonious Monk, through whom I met Clark Terry, and thus Cannonball-who was the first man to turn me on to Wes Montgomery, and so on and on). I liked the men, and it seemed pretty mutual; and I liked their music, but not nearly enough other people did, because by late '57 the first Cannonball Adderley Quintet had disbanded. It was not at all a bad band (the brothers' rhythm section was Junior Mance, Sam Jones, and Jimmy Cobb), but the time wasn't right yet, or something, and they drew such slim audiences that, according to Julian's deadpan account, their best weeks were the ones they didn't work-"At least then we broke even." The breaking up of that quintet turned out to be far from disastrous. Just consider the aftereffects. For one thing, Cannon decided to put in some time collecting a salary without leadership headaches, and so he accepted Miles's job offer, a key step in the formation of probably the most significant and influential band in modern jazz: the sextet with Adderley, Coltrane, Evans, Chambers, and Philly Joe. Secondly, the Adderley brothers blamed their record company to some extent for their band's failure and Cannon began to take steps to terminate what proved to be a somewhat ambiguous contract with Mercury. By this time he was getting lots of moral encouragement from me, and Riverside (which had Monk, and Bill Evans, and a couple of Sonny Rollins albums) was looking like an increasingly interesting label, and in June of 1958 he signed a recording contract with us. What I remember above all from the meeting at which the signing took place was that Cannonball was accompanied by his personal manager. I don't think I had ever before dealt with a musician who had a real honest-to-God professional manager. Hell, Julian was only a sideman at that time, and the contract involved the lowest imaginable advance payments, and we even used the standard printed form contract that the musicians' union provided. But there was a manager (John Levy, eventually one of the busiest and best, and associated with Adderley forever after) and there was one special condition. Mercury, it seems, had only recorded Cannon's working group once (and hadn't issued that album until after the group broke up). So I promised that, as soon as Julian re-formed a band, and just as soon as he felt it was ready to record-whenever and wherever that might be-I would go there and record them. An interesting verbal commitment: a nonexistent band would be promptly recorded someplace on the road by a still very shoestring company that had never sent its staff producer, me, to work any further than a subway ride away from home. But it turned out to be one of the neatest examples of the good results of bread-cast-upon-the-waters since the Bible. Cannonball began by recording some strong albums for us (the first two, combined now on Milestone 47001, involved men like Milt Jackson , Bill Evans , Art Blakey, Wynton Kelly-both because of Cannon's taste in picking sidemen and because of good players' desire to associate with him). Then by mid-1959, he was ready to make his move, to leave Miles and reshape his own band. Inevitably that meant Nat ; and just about inevitably their longtime Florida buddy, Sam Jones, on bass. In those days, when there were a great many regularly working groups out there, it was hard to put together an experienced unit without raiding other bands. Julian wasn't happy about this, but he knew what drummer he had to have, and so he rather reluctantly forced himself to steal Lou Hayes away from Horace Silver. He was a bit more indecisive about the piano slot: for a while he favored Phineas Newborn, and I remember going with Julian to Birdland one night to hear him. Newborn, always an impressive technician, was pretty overwhelming that night, and he was offered the job. But, Cannon in formed me, Newborn had one impossible demand: he wanted featured billing. The trouble was, Nat was already guaranteed that-and how could you have a leader's name and two featured artists in what was only a five-man group without the other two feeling an awful draft. He just couldn't do that to Sam and Louis, Cannon said. So he turned to his almost-first choice and enticed Bobby Timmons away from Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. And everyone concerned was very soon damn glad he did, for the cocky young pianist/composer, whose "Moanin' " had been a 1958 winner for the Blakey band, immediately came up with another one. After breaking in act or two weeks in Philadelphia, the quintet went to San Francisco for three weeks at the Jazz Workshop. But even before they left for the West I had been put on notice that the "whenever and wherever" I had promised was going to be then and there. The band was together; the first audience reactions to Timmons's new tune, This Here," had convinced Adderley that he had a hit; and what was I waiting for? If I'd had the sense and experience to know what to worry about, I'd have recognized plenty to wait for: among other things, San Francisco at that time had not a single recording studio; there were very few engineers anywhere with a command of the fledgling art of recording "live" in a club; and in any event I didn't know a single engineer in that area. But a promise is a promise, right? So I asked Dick Bock, head of the Los Angeles-based Pacific Jazz label, for advice, and he recommended a young man who, he informed me, had recently done a live recording for him in the very same club. (Dick neglected to tell me he had decided the session hadn't come out well enough to be issued.) Not to prolong the suspense: I found my way to San Francisco (incidentally beginning my still-heavy love affair with that city); I heard "This Here" for the first time (and was informed by the late Ralph Gleason that the audience reaction was that hectic every night); we recorded for a couple of nights and came up with a lovely album. Those nights were my first opportunity to really study Cannon as a bandleader, and thereby to discover the remarkable secret of his appeal. The way I saw it, Julian was one of the most completely alive human beings I had ever encountered. Seeing and hearing him on the bandstand, you realized the several things that went to make up that aliveness: he was both figuratively and literally larger than life-sized; he was a multifaceted man and it seemed as if all those facets were constantly in evidence, churning away in front of you; and each aspect of him was consistent with every other part-so that you were automatically convinced that it was totally real and sincere, and you were instantly and permanently charmed. That last paragraph is the emotional way of saying it; if I try real hard I can be more factual and objective. He was a big man and a joyous man. He was a player and a composer and a leader, and when someone else was soloing he was snapping his fingers and showing his enjoyment, and before and after the band's numbers he talked to the audience. (Not talking at them or just making announcements, but really talking to them and saying things about the music- some serious, some very witty.) So all that whirlwind of varied activity was always going on when he was on the stand, and it all fitted together, and you never even considered the possibility that it could be an act. Of course it wasn't; it was (to use today's cliché) just Cannon doing his thing; and part of his thing was wanting you to enjoy yourself;and you did His talking to the audience was then (and remained) pretty unique;in assembling that first Jazz Workshop album i somehow got the daring idea of not only including some talk but giving it the same position on record that it had in the club. So that album opened with almost a minute and a half of Julian conversing about "This Here" before you heard a note of music, and apparently it was a good idea, or at least it didn't hurt, since the album turned into a huge hit. It established Cannon and the band and the adventurous label that had gone cross-country to make the record. (And it and its imitators led, for better or worse, to a whole flood of "soul" jazz.) We were all successful and very happy with each other. We stayed with the formula a lot-there were four other "live" band albums on Riverside -and years later, when he had an even bigger hit for Capitol with "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" he explained it to me as "I finally talked Capitol into recording me the right way; the way you and I used to do it." In this ego-heavy music business, how can you not love a man like that? Well, some people could manage to not do so, I guess. There were the usual put-downs by the critics (success really doesn't automatically mean you're not playing as well as before, but . . .); and there were similar put-downs by less successful musicians. Those had the power to hurt his feelings at times, but not always; for example, what could we do but laugh at the jazz giant who said that "This Here" was nothing more than rock and roll and then quickly added that anyway it was stolen from one of his compositions. On the whole, however, there was a lot of approval and those were good times. Riverside in the Cannonball years was a very happy place; there was an unprecedented team spirit among the musicians working for the label, and Julian was very much a leading part of that. He was, as has often been recounted, responsible for our "discovery" of Wes Montgomery: he had heard Wes in Indianapolis one night, and as soon as he got back to New York came bursting into my office insisting that "we've got to have that guy on the label." Allow me to tell you that there are hardly any performers around at any time who are going to refer to the company they are under contract to as "we." He was the kind of star who volunteered his services as a sideman (at union scale) for the record dates of men he liked and respected: Jimmy Heath, Kenny Dorham, Philly Joe Jones. He came up with the idea of his producing albums that would present either unknown newcomers or underappreciated veterans; he felt that his name might help their careers. (Chuck Mangione first recorded as a Cannonball Adderley "presentation.") He was an intensely loyal man, and he inspired loyalty. In the 16 years between the re-forming of his quintet and his death, he had only two drummers (Lou Hayes eventually being succeeded by Roy McCurdy-who had been the drummer on the first Cannonball-produced Mangione album), and not very many more bass players. There were a few more piano players: Timmons left to return to Blakey and then go out on his own; a couple of others didn't quite work out; Cannon was never able to persuade one of his major personal favorites, Wynton Kelly, to work in the band; but Joe Zawinul, who joined him in the very early Sixties, stayed around for a long time. My own strongest recollections of his loyalty relate, not too surprisingly, to when his contracts with Riverside were running out. The first time, in 1961, he was a very hot artist and we were pretty resigned to his being seduced away by major-league money. We made our best gesture-and he took it, even though it turned out to be much less than at least one major label had offered. The reason he gave, that he felt comfortable and at home among friends with Riverside, was just corny enough to be obviously true. Even more impressive was the way he behaved the Spring of '64. The label was then almost on the rocks: after the unexpected death of my partner it became clear that Riverside's financial picture was much more precarious than anyone had realized. I was fighting for survival, and losing. So Julian volunteered that, regardless of what any other companies might come up with, he'd simply extend his contract with us for another year. It could be announced as a re-signing, and obviously the news that we were retaining our top- selling artist would be a big help. I wrestled with the idea: the main trouble was that Riverside was mortgaged up to slightly above eye-level. We were at the mercy of financial types whose shifting attitudes made it quite likely that the label was simply beyond being saved even by Cannon's play. It was a very strange situation: he kept offering and I kept hedging, and eventually one day I called him and said, in effect: "This is final; we're not going to be able to make it, so don't stay with us. Even if I call you tomorrow with a different story, don't pay any attention. This is the final true word: go away. Even then he was reluctant; and how many major artists can you think of that a record company would have to practically chase away with a club. (I was right, incidentally ; about ten days after his contract was allowed to run out, Riverside closed its doors.) For about eight years thereafter, we succeeded in the very tricky art of being ex-co-workers who remained friends. Sometimes we didn't see each other for long periods of time; on other occasions we got around to talking at great length on both musical and nonmusical subjects. Most musicians I have known are (understandably enough) so wrapped up in themselves and their art that the rest of the world just doesn't hold their interest. (The polite way to describe this is by saying that artists are nonpolitical beings.) But Cannon happened to be vitally interested in all of life; he enmeshed himself in a wide variety of activities. He was also one of the few people I have ever come across who could consistently talk as much as I do. I'd say that his old friend Pete Long and I were only partly joking when we claimed that someday we were going to run him for Senator. Cannon and I also came up with some intriguing musical ideas that we never did anything about. My favorite remains our plan to collaborate on a musical comedy based on the life of Dinah Washington. It is still easy for me to hear his vivid description of one potential scene, backstage at the Apollo Theater, with Dinah's dressing room filled with a procession of stolen-goods salesmen ("everything from hot fur coats to hot Kotex.") Eventually, fate moved our professional lives back together: I joined the Fantasy organization; Cannonball signed with Fantasy; and the company also acquired domes tic rights to the Riverside catalog. After a while we got back to working together. He and Nat and I began by co-producing a package that was a real natural for us-new reworkings of the best material from the good old days (as far back as "This Here" and "Work Song" and "Jive Samba"). Working together again felt natural and good; I gave the album a title intended to reflect the comparative immortality of a man who had been a jazz star for all those years and was still going strong. But Phenix-the reference is to the legendary bird that is reborn every few hundred years out of the ashes of a self-consuming fire-turned out to have more irony than prophecy to it. Only a few months after its comple ion, and while his next album remained unfinished, Julian had a stroke and, at the devastatingly young age of 46, was gone. Cannon was certainly not a man without faults, but none of them were petty and the ones I was aware of were strictly self-injuring and directly connected with his huge love of life. He ate a lot (often his own food-he was a great cook) and drank a lot, and that's not really a good idea if you also happen to have high blood pressure and a touch of diabetes and a definite tendecy to overweight. But there was no way in the world that he was going to scale himself down and be practical and cautious about his health. It would have been nice if he could have done so; most probably we'd still have him around now; but I'm afraid it just wasn't in his nature to play it that way. And considering how much joy and warmth and creativity specifically came from that nature, how can any of us who knew and loved him complain too hard at the way it worked out. We can and do deeply mourn the unfair, untimely loss; but we also have the still-vital memory of him. And we have his music-and one very good thing about this music is how accurate a picture of the man it has always given. That means the music will help keep Cannonball extremely alive for us; and that's not bad at all.

Orrin Keepnews has been producing jazz records, and frequency writing about them, for the past two decades.

A note on the contents of this double-album: In 1963, one of Cannonball's finest groups-four original members plus Joe Zawinul on piano and with the addition of Yusef Lateef making it a wonderfully strong sextet-made a Japanese tour highlighted by several concerts in Tokyo. Riverside issued one album of material recorded at that time. There were a number of equally impressive performances that remained unissued simply because other versions of those tunes had recently been released on other albums. The passage of time has of course made that distinction irrelevant, and we can now include five "new" items, in cluding such gems as this version of "Jive Samba" and the only sextet recording of the classic "Work Song." This compilation produced by Orrin Keepnews. Sides 1 and 2 remixed in 1963 by Ray Fowler (Riverside Records; New York City) from three-track original tapes; remastered, 1975, by David Turner (Fantasy Studios; Berkeley, Ca.). Sides 3 and 4 remixed in 1975 by Jackson Schwartz (Fantasy); mastered by David Turner. Art direction-Phil Carroll Cover photo-Bruce Talamon

|