|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

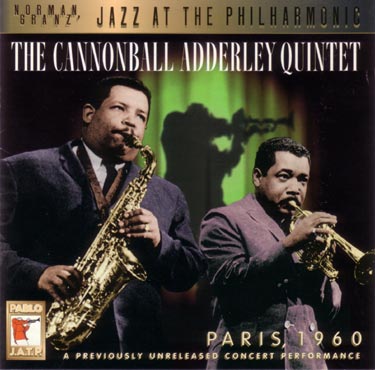

"JATP Paris 1960" |

![]()

|

CANNONBALL ADDERLEY -alto sax

NAT ADDERLEY -cornet

VICTOR FELDMAN -piano

SAM JONES -bass

LOUIS HAYES -drums

|

Jeannine (Duke Pearson)

9:14

These recordings, the first new Cannonball Adderley performances to be legitimately issued for well over a decade, mark a remarkable and long-overdue renaissance for perhaps the most distinctive hard bop alto saxophonist of his generation. He was certainly the most articulate and, after a long hiatus, he is turning out to be perhaps the most influential, with his style being used intelligently as a base by many young alto players who have emerged in this fin de siècle-men like Antonio Hart, Vincent Herring (who played in the quintet led recently by Mr Adderley's brother, Nat), and the late Art Porter, among others. Julian "Cannonball" Adderley's own twenty-year career ran to a pattern common in jazz. He began more loved by musicians and critics than by the public, and ended more loved by the public than the critics. In between was an intense period when, first with Miles Davis, then with his own re-formed quintet, heard here, Cannonball was lauded by both camps for his individuality of style and his melodic expressiveness, particularly with standards and the blues. However, Mr. Adderley retained a sunny disposition in much of his work, even the blues, echoing that of the trumpeter Clifford Brown. Despite a rare eloquence in his playing, this deflected many commentators from recognizing his obvious gifts with the blues, and so they casually wrote him off as of narrow emotional range. The extent to which this was untrue is amply demonstrated on every performance from this exciting concert. It stems from a particularly significant period in Mr. Adderley's life, which itself began in Tampa, Florida, on September 15, 1928. Adderley had on graduation 20 years later turned to teaching rather than to playing full-time, initially ignoring the blandishments of his younger brother, the cornet-playing Nat who, in 1954, traveled with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. In 1955, however, Cannonball ventured to New York to work on his master's degree during school vacation and there followed one of the legendary incidents in jazz history. As brother Nat remembers it: "My friend Buster Cooper [the Ellington trombonist] took us to the Cafe Bohemia to hear the Oscar Pettiford band. By chance, their saxophonist was absent doing a record date and Julian was spotted at the back with his alto. Oscar sent Charlie Rouse over to borrow the horn, but Charlie had met Julian in Florida and instead sent him up to the stand to sit in." Oscar Pettiford gave this chubby unknown youngster an old-fashioned look then counted off the standard "I'll Remember April" at a finger-busting tempo. "Cannon sailed through this and the next tune and, two nights later, he joined the hand full-time," Nat recalled. It ended Cannonball's teaching career ,but not before he had returned to Florida to fulfill his high school contract for the fall term. Then, early in 1956, he and Nat formed their first quintet. It lasted nearly two years until, fed up with poor drawing power compounded by poor support from their record company, Cannonball joined Miles Davis in what would become perhaps the most influential band of the late 1950s, the sextet with John Coltrane and Bill Evans. Towards the end of 1959, the time seemed ripe to re-form their own band and, with virtually the same personnel and repertoire as before, the "Cannonball Adderley Quintet featuring Nat Adderley" again hit the road. The difference was their pianist, Bobby Timmons who, during their first major engagement, at San Francisco's Jazz Workshop, produced a new tune, "Dis Here." This and the album that included it (In San Francisco, OJCCD-035-2) defined "soul jazz" and sold tens of thousands of copies, elevating the Adderley band into the premier league of jazz earners and setting the seal on the attacking, bluesy approach which was replacing the more effete West Coast styles that had dominated the previous decade. The Adderley quintet was now a phenomenon and it is this phenomenon that is heard on these previously-unissued recordings from the same tour that produced What Is This Thing Called Soul? (OJCCD-S01-2). That disc presented performances from concerts in Sweden a few days earlier in this tour, Mr Adderley's first outside the U.S.A. His band was traveling as part of a Norman Granz-organized Jazz At The Philharmonic package that also included one of Adderley's principal influences, alto saxophonist Benny Carter, as well as the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet, Stan Getz, Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas, Roy Eldridge, and J.J. Johnson. For two weeks, European audiences -packed auditoriums in Holland, Germany, Sweden, Britain, and France, all eager to hear this new sensation. Keen anticipation was sharpened by the fact that the band's new Riverside recordings were not being distributed in Europe at the time (that would follow within six months). But the reality drew complaints-not about the quality of the music, which was universally applauded, but about the presentation by Norman Granz. Adderley's band had been designated to open proceedings at each concert, but, because of Granz's predilection for all-star mix-and-match lineups, it was restricted to three or four tunes in each set. Criticism of this by reviewers, many of them jazz musicians like Swedish pianist Lasse Werner and Swiss drnmmer Daniel Humair, appeared too late to change this but, as so often, out of concentration comes the powerful essence of a band. And so it was here. The music here is drawn from both the concerts played this night at the Salle Pleyel and tour organizer Norman Granz is heard first, introducing the musicians. A huge and significant friend of jazz through his patronage, his Clef, Verve, and Pablo record labels, and his concert tours, Mr. Granz inadvertently underscores the rarity of Nat's preference for the cornet in the modern idiom by introducing him on trumpet. Once the music stomps off, what is immediately on display is Cannonball's easy virtuosity, a tonality that is more Benny Carter than Charlie Parker, but a melodic verve firmly rooted in the modern bop and hard bop era of the 1950s and 1960s. His is a style of plump, relaxed fluency, with instantly recognizable and highly individual trademarks, like those memorable phrases that curl up their toes as they melt into the next sequence. Alongside, in what Cannon invariably referred to as "our brass section," brother Nat has rarely received his dues as one of the most accomplished trumpet/cornet players of that period- and any other since-combining the virtues of Dizzy Gillespie and Clark Terry in an individual manner that was occasionally (and ludicrously) mistaken for Miles Davis. In the rhythm section, British pianist/ vibist Victor Feldman had joined a few months earlier, bringing an articulate single-noted and block-chording style that was closer to Wynton Kelly than his predecessor, Bobby Timmons. The Adderleys were particularly taken with his compositions, which, like "The Chant," fattened the band repertoire. Sam Jones was a family friend from Florida, but also one of the best bassists around and known as "Home" for his soulful phrasing, while the crackling drums of Louis Hayes had been lured from the 1959 Horace Silver Quintet. "Jeannine," from the quintet's second Riverside album, Them Dirty Blues (1960), is a fleet but singing line by pianist Duke Pearson, who was concurrently featuring it in the Donald Byrd Quintet. As Adderley tells this audience: "You know, tunes named after girls like Jeannine are usually slow, wispy ballads, but this Jeannine is a swinging chick, right?" "Dis Here" is Adderley's "One O'Clock Jump"-an instantly-recognizable signature, written in the blues but taken in then-rare triple time. Nat's brief strict-timing on a famous ballroom waltz should not obscure the fact that this tune repays careful listening. As Cannon himself was wont to point out, its apparent simplicity was deceptive, so it is entirely apt that it should end on a musical question mark. Next up is another waltz, trombonist Frank Rosolino's more somber "Blue Daniel," which the Adderleys had debuted in an album recorded the previous month at Rosolino's old haunt, the famous Lighthouse on Hermosa Beach in California. Victor Feldman's hot-gospeling "The Chant" is as down-home as you can get, despite its composer's origins, Sam Jones's equally down-home bass staking out the congregational responses to the preaching horns. Remarking on his pianist's Englishness, Mr Adderley once observed: "He isn't supposed to have this kind of soul because it's the other kind of soul." "Bohemia After Dark" is the other test piece Adderley faced that first night in New York when he sat in with the Oscar Pettiford Sextet and named for the New York nightclub where that took place. With a war-dancing bridge inspired by Mr Pettiford's native American origins and a snaky melodic line it was a tune test, but here taken twice as quickly as Mr Adderley's original recording five years earlier. More than any other performance here it demonstrates Adderley's inventive fluency at any tempo. The set ends with another of the Adderleys' soul signatures, Nat's "Work Song." Reflecting the call-and-response blues of the chain gang, it receives a jaunty treatment that sits alongside the existing studio versions by both brothers more than satisfactorily. The crisp and sprightly cohesion of this band strongly reflected the Adderley ethos that his band was like his family. This was underlined by an extremely low turnover of players: from 1959 to 1975 it had only two drummers, just four bassists, one pianist remained for ten years, and, of course, there was always just one cornetist and one alto saxophonist! There was, however, a shadow lengthening over his life. Mr. Adderley was a diabetic and, although he was happy to tell audiences about this awkward fact of life from time to time, it seems not to have been widely known. It caused the weight problems that occasioned Down Beat magazine invariably and insensitively always to refer to him as "the rotund saxophonist." And, in the end, it was this condition that claimed his life in the summer of 1975 at the age of 47, just as it did the lives of other important alto players, notably Eric Dolphy and Julius Hemphill. Like them, Mr Adderley left a rich and rewarding legacy of recordings, some of which have remained undiscovered treasure until now.

|