![]()

"ALABAMA CONCERTO" |

![]()

|

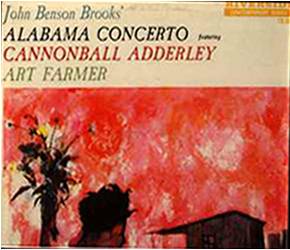

John Benson Brooks'

ALABAMA CONCERTO

featuring CANNONBALL ADDERLEY

Art Farmer, trumpet; Julian (Cannonball) Adderley, alto sax; Barry Galbraith, guitar; Milt Hinton, bass.

John Benson Brooks, piano (in third movement only).

Recording directed by John Benson Brooks. New York; July and August, 1958.

SIDE 1

1. First Movement (11:03)

themes: The Henry John Story ; Green Rocky Breasts (Nature!) ; Some Lady's Green ; Job's Red Wagon

2. Second Movement (10:08)

themes: Trampin' ; The Loop

SIDE 2.

1. Third Movement (8:19)

themes: Little John Shoes ; Milord's Calling

2. Fourth Movement (10:07)

themes: Blues for Christmas ; Rufus Playboy ; Grandma's Coffin

It is doubtful whether there has ever before been a musical work quite like this Alabama Concerto, with its bold fusing of jazz virtuosity, folk-music themes, and what is usually called "serious" composition.

"Serious" is a proper word here, and so is "concerto," for this is music by a schooled, richly creative writer, and it does follow the classic concerto form. But these words should not be allowed to frighten anyone: John Benson Brooks is an adventurous, highly melodic, often extremely witty composer; and his concerto departs from traditional form in being designed to permit quite a lot of free-blowing improvisation by the four jazzmen on hand - particularly by the forceful, blues-based alto of CANNONBALL ADDERLEY and by ART FARMER's firm-toned, graceful trumpet.

Brooks, whose background includes service as an ar ranger for such as Les Brown and Tommy Dorsey and who has been a writer of pop song hits (Just As Though You Were Here, You Came a Long Way From St. Louis, etc.), has in recent years been devoting himself to more ambitious projects. With such other composer-arrangers as Gil Evans and George Russell, he forms what can loose ly be grouped as a "school" of modern jazz writing: For although procedures and emphases may differ, these writers are all joined by a concern for developing and advancing the form of jazz without sacrificing its spirit. Possibly the most distinctive feature of Brooks' particular approach is his resQlute rejection of the standard format and chord structure of "popular music" on which so much of jazz has always relied, and his turning for source material, as in this concerto, to the bedrock of folk-music.

Specifically, Brooks notes that "the history of this piece must begin with an anthropological field trip Harold Courlander made to Alabama several years ago. He recorded a whole Negro community: children's game songs, blues, hollers, spirituals and odd bits." Brooks was given the job of transcribing this material for a book, and found himself hopelessly fascinated. "One thing that struck me was the light cast on jazz origins. A different taste from New Orleans' urban finery. Apparently jazz is a much more deeply-rooted characteristic of American life than has been generally recognized."

What Brooks learned from these rural survivals about the vital role of pre-jazz folk music in the initial formation of jazz, has been combined with his creative talent as a composer and his deep understanding of jazz to create something unparalleled and richly rewarding.

"In using some of these musical themes for a jazz com position," he notes, "I took the concerto, which is the simplest large form, traditionally featuring essentially only themes, returns of themes (ritornelli), and an ad lib cadenza. In this particular piece it seemed most feasible to have four elements of approximately equal proportions: ensemble playing, combinations of two or three of the instruments, written solos, and improvised ad libs."

To perform such a work properly, all that was needed was four jazzmen who could read like demons and 'blow' like angels. Rather surprisingly, they were not too hard to find, and it is the composer's feeling that these four added much to the piece as it took firm final shape during actual recording. Barry Gaibraith and Milt Hinton are thoroughly experienced, versatile rhythm men, both of whom graduated from big bands into studio indispensability without ever losing either soul or the ability to swing. Art Farmer combines a great deal of lyricism and sensitivity with a rare ability to read and execute flaw lessly the most difficult of written scores. Julian Adderley is a formidable altoist, most recently featured with Miles Davis. His reputation has heen largely as one of the most remarkable improvisors of our day, but Adderley is actually a thoroughly schooled musician (and one-time music teacher), and his command of the Brooks score is scarcely less impressive than the flow of his ad lib solos.

The titles of the various themes (as listed in the box) were initially devised by Brooks as private working titles. solely for his own guidance. Created, for the most part, by off-beat twistings of the names of songs from which the themes were derived, they may seem none too mean ingful, even flippant, when read before listening. But try coming back to them after hearing the concerto and you'll very probably agree that they are most apt and interesting indications of the mood and flavor of Brooks' work. (Titles or opening lines of the original source material themes are given in Brooks' notes, just below.)

The composer's own descriptive commentary on the progression of the piece makes up an unusually flavorful and heipful set of program notes -

First Movement: The opening is built on John Henry (today you might say, The Henry John Story) - Cannonball's ad lib concludes and Art introduces the second theme (Some Lady's Green, Green Rocky Roud). Milt walks down to close it, and the third theme (Job, Job) enters in tempo change and exits in parody.

Second Movement: The opening is made of Trampin' (an old spiritual). It concludes in bowed bass and pianissimo guitar and Milt then brings in The Loop. This was a children's game song (Here We Go Loop de Loo) that reminded me of Pres but ac quired a boppy episodic melody based on four sets of tonics. Cannonball closes it asserting the Trampin' ritornello and then The Loop returns in slower pace, eventually culminating in a "collision" (It had never occurred to me that the end is some times just that.)

Third Movement: This has piano in the initial conversation and close in group forte (Move, Members, Move!). Guitar and bass bring in its companion theme (Didn' You Hear My Lord When He Cried?). The returns on these themes continue the relaxed horn improvisations.

Fourth Movement: The What Moonth Was Jesus Born In? opening features the months and concludes with Milt walking through a few bars into Barry's statement, through the horns, of Hey, Rufus ("hey, boy, where in the world you been gone so long?"). The third theme (Rock, Chariot, I Tol' You to Rock) sneaks into the first ending of Art's chorus on Rufus and again in the second ending - Cannonball picks it up and segues into the return of What Month. The Rock, Chariot theme returns in his marsh-horn call. Art interrupts Cannonball's ad lib with the Hey, Rufus return and Cannonball does the same later (two AABA's) the rest of the movement being a play between Rufus and the Chariot.

A HIGH FIDELITY STEREOPHONIC Recording-River

side-Reeves SPECTROSONIC High Fidelity Engineering. Produced by

ORRIN KEEPNEWS and BILL GRAUER. Notes by ORRIN KEEPNEWS. Cover

painting: "Wild. flowers," by WALTER WILLIAMS. Cover

designed by PAUL BACON. Engineer: JACK HIGGINS (Reeves Sound

Studios).