|

|

| Discography |

| About Julian |

| About Site |

Since Dec,01,1998

©1998 By barybary

![]()

|

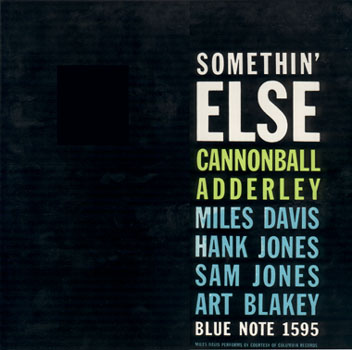

"SOMETHIN' ELSE" |

![]()

|

JULIAN CANNONBALL ADDERLEY

MILES DAVIS, trumpet;

HANK JONES, piano;

SAM JONES, bass;

ART BLAKEY; drums.

SIDE A

|

AUTUMN LEAVES 10:58 |

LOVE FOR SALE 7:03

SIDE B

SOMETHIN' ELSE 8:12

ONE FOR DADDY-O 8:21

DANCING IN THE DARK 4:04

ON CD Reissue and on Special Limited edition 45 rpm (Japan)

ALISON'S UNCLE (Bangoon) 5:05

ON CD Blue Note TYCJ 81002 75th

Anniversary reissue series

and Lp Vinyl Lovers – 6785516 (2019)

AUTUMN LEAVES (Alt Takes ) 9:33

|

Recorded march 9,1958 , Hackensack, NJ |

|

WHAT manner of album is this? Julian Cannonball Adderley, the leader of the group that remains so ardently aflame throughout these sides, is an alto saxophonist cast in the Charlie Parker bop mold. Miles Davis, the other half of the front line, has been the subject of learned dissertations in which he is identified with a branch of jazz known as cool music. And Hank Jones, whose piano is the third important voice in the quintet, has spent a substantial part of the past two years as a sideman with a big band led by the King of Swing. Art Blakey's drums have been associated with an alleged new school that has variously been billed as "hard bop" and "hard funk." As for Sam Jones, bass, he is Sam Jones, bass, though lately there has been a tendency to categorize and pigeonhole even the bass players. What is remarkable about the above-cited facts is not that members of various schools have been able to assemble and collaborate in the production of a superlative jazz album, but rather the fact that they are not really as various as the critics might have you believe. Both Cannonball and Miles agree that there has been far too much labeling of jazz-men, that there is an almost limitless degree of overlapping between schools, and that what counts is not the branding of the music but the cohesive quality of their concerted efforts. Only three years have elapsed since Cannonball fired his initial salvo at the Gotham scene. He would have been unable to sit in on the important night that marked his New York debut had not school been out. School to Julian Adderley meant Dillard High in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where he had been band director since 1948. Wandering north, he and his brother Nat found themselves at the Bohemia, where the incumbent group was Oscar Pettiford's combo. It happened that Jerome Richardson had not yet arrived for work, but Julian's offer to step into the spotlight was greeted with some wariness by Pettiford, who had never heard, or heard of, the plump, cheerful-faced newcomer. To put him in his place, Oscar beat the band off with I'll Remember April at an impossible tempo. But Cannonball had come up in the Parker school that knows of no tempo impossibilities. He met the challenge with a long solo that just about knocked Pettiford off the stand. Soon the word spread around town, and before many days had passed Cannonball's recording career had begun. By the following year he had earned enough acclaim to enable him to renounce the academic life in favor of a full-time jazz career, touring with his own quintet. Julian Cannonball Adderley (the name has nothing to do with ammunition; it is a corruption of cannibal, a nickname given him in tribute to his healthy appetite) was born September 15, 1928, in Tampa, Fla. His music studies at high school and college in Tallahassee between 1940 and '48 gave him a solid background first on trumpet, later on various reed instrument He has been a bandleader off and on for the past decade, generally as a sideline during his years at Dillard High, and in 1952-3, while he was in the Army, as leader of a large dance band as well as a small group. During a recent television appearance, when he was introduced as a representative of bop in the NBC educational series The Subject Is Jazz Cannonball was interviewed concerning his original reaction to Bird. "Well," he said, "I listened to all the other alto players, and some of them were fine, but there still seemed to be something lacking. When I first heard Bird, I knew immediately that that was it. His style was completely original, far ahead of anything I had heard, and his harmonic sense was unorthodox." From that point on, the impetus and inspiration behind Adderley's work was almost exclusively Charlie Parker. Despite the apparent disparity between the hard-hop approach of Cannonball and the supposedly cool personality of Davis, their collaboration (Adderley broke up his own quintet to loin Miles in late 1957) seems quite logical in the light of Miles' own background, since he was a partner of Bird himself in the Parker quintet during its early years and can be heard on many of Bird's earliest and greatest records It seems useless to add anything about the contribution to jazz of Miles, probably the most influential trumpeter alive in terms of impact on the present musical generation. What he had learned originally from Clark Terry and others in and around St. Louis he later expanded when he heard Vic Coulson in New York ("it was impossible to try to play like Dizzy, so I listened to Vic") - All this experience was slowly leavened into a new personality; what had been a hop partnership with Charles Parker grew into an individual ownership, a talent that knew the virtues of understatement as well as the beauties of a more directly assertive expression. Today Miles finds orientation and guidance in a variety of sources, some of them unlikely, or at least unexpected: "All my inspiration today," he asserts, "comes from Ahmad Jamal, the Chicago pianist. I got the idea for this treatment of Autumn Leaves from listening to him." Autumn Leaves, an extended treatment that invests the composition with a great deal more complexity and elaboration than has ever been heard on any previous version, starts out in a long introduction as an apparently unidentifiable G Minor melody. Miles brings in the theme, followed by Julian; later there is an ad-lib interlude by Hank Jones suggested by Miles, and a return to tempo at a slightly slower pace. Blakey remains discreet and tasteful throughout. The performance closes with another passage that seems to float in mid-air on a nameless minor theme, built around three triads: C Minor, A Minor, and B-Flat Major. Love for Sale opens with a pretty ad-lib Hank Jones introduction. Miles' opening statement of the theme is muted and spare, ending the first 16 measures on a moody 9th. There are Latin interludes throughout as the three soloists take turns at the microphone; a repeated riff fades out at the end. Cannonball's solo on this track is perhaps the most typical of all in the set: the big, round sound, the Parker-oriented phrasing and harmonic sense, consistently interesting linear development all are in evidence. Somethin' Else is, to me, the most exciting of the five mood-evoking tracks in this set. It establishes at once, and sustains throughout its considerable length, a certain mood of restrained exultancy, a low-glowing Davis fire that burns contemplatively until stirred to even greater warmth by the embers of Adderley's stimulation. The performance begins with Miles uttering short, simple phrases, mostly between the tonic and dominant of the scale, all answered in echo-and-response style by Cannonball. Though the construction of the piece is the traditional 12 measures in length, its harmonic movement is unconventional and strikingly effective in its creation of a mood. Starting out on F-7th with a flat 5th, it proceeds to D-raised 9th flat 6th, C-raised 9th flat 6th, B-Flat-7th flat 5th, then back to the D-raised 9th, C-raised 9th, and finally moving from C to D to the tonic F. Hank's solo on this one is in block-chord style. "That delicate touch of Hank's," says Miles "There's so few that can get it. Bill Evans and Shearing and Teddy Wilson have it. Art Tatum had it." And in tribute to Art's manner of swinging the rhythm section he adds," Sonny Greer used to swing like that with sticks and brushes in the Ellington band in the old Cotton Tail days" One for Daddy 0 dedicated to the popular Chicago disc jockey Daddy-O Daylie and composed by Cannonball's brother, Nat, returns to the 12-bar theme but this time closer to the traditional funky blues spirit, with an inspiring and inspired beat. After the theme it is transmoded into a minor blues with Julian alternating between simple phrases and double time statements Miles solo starts out simply with a plaintive use of the flatted 7th in measures nine and ten of his first chorus; a couple of choruses later he reached higher than we are normally accustomed to expect from a trumpeter generally associated with the middle register of the horn; but the upward movement clearly is a natural outgrowth rather than a contrived effect. Some months ago there was a complaint, in a misinformed and insensitive article that appeared in Ebony, that "Negroes are ashamed of the blues." The white author of the piece would doubtless be incapable, on hearing this Davis solo, of perceiving the porcelain-like delicacy of his approach to the blues. Certainly this is not the blues of a man born in New Orleans and raised among social conditions of Jim Crow squalor and poverty, musical conditions of two or three primitive chord changes; this is the blues of a man who has lived a little; who has seen the more sophisticated sides of life in Midwestern and eastern settings, who adds to what he has known of hardships and discrimination the academic values that came with mind-broadening experience, in music schools and big bands and combos, in St. Louis and New York and Paris and Stockholm. This is the new, the deeper and broader blues of today; it is none the less blue, none the less convincing, for the experience and knowledge its creator brings to it. Far from being ashamed of the blues, Miles is defiantly proud of his ability to show its true contemporary meaning. Hank has a couple of solo passages, one in single-note lines, another making economic use of thirds and fourths. After the performance has reached its clearly successful climax Miles can be heard asking for a reaction from the control booth. It need hardly be added that Alfred Lion got just what he wanted. Dancing in the Dark is Cannonball's individual showcase. "I made him play this," says Miles, "because I remembered hearing Sarah Vaughan do it like this." It might be added that in Julian's two choruses, since he is not restricted to a prescribed set of lyrics, he does even more with it than Sarah was able to do. In closing perhaps it would be appropriate to point out, for those not familiar with the latest in terminology, that the title number of the Miles Davis original, which also provided the name for this album, is a phrase of praise. And if I may add my personal evaluation, I should like to emphasize that Cannonball and Miles and the whole rhythm section and, indeed, the entire album certainly can be described emphatically as "somethin' else." -LEONARD FEATHER Author of The Book of Jazz Cover Design by REID MILES Photo by Fancic WOLFF Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER

|